I. Background and Objectives for the Systematic Review

According to Census data, 86 percent of women in the United States will give birth at least once by age 44.1 The risk of a psychiatric illness during the perinatal period is substantial. New-onset psychiatric disorders during the perinatal period (immediately prior to pregnancy, during pregnancy, and through 12 months postpartum) may be difficult to quantify accurately because most women with a psychiatric condition do not receive mental health care, regardless of pregnancy status:2 many women's first encounter with the healthcare system may be in the context of their pregnancy. Results from a large epidemiological survey in the United States offer indirect evidence on rates of new onset in the perinatal period. The study compared the prevalence of mental health disorders in past-year pregnant women (pregnant at the time of the survey or pregnant in the prior 12 months), postpartum women (a subset of past-year pregnant women who were pregnant during the prior 12 months but not at the time of the interview), and non-pregnant women of child-bearing age.2 Among past-year pregnant women, the study reported prevalence rates of 13.3% for any mood disorder (including major depressive disorder [8.4%], dysthymia [0.9%], and bipolar disorder [2.8%]), 13% for any anxiety disorder (including panic disorder [2.2%], social anxiety disorder [1.8%], specific phobia [9.2%], and generalized anxiety [1.3%]), and 0.4% for any psychotic disorder (including schizophrenia). The study reported no statistically differences for depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder or psychotic disorder between past-year pregnant women and non-pregnant women. The study did find significantly higher odds of depression among post-partum women when compared with non-pregnant women. However, some uncertainty persists as to whether higher rates of postpartum depression reflect poor identification during pregnancy rather than new onset of the disorder in the postpartum period,3 and whether the differences in rates of depression between past-year pregnant women and nonpregnant women might be understated.4 The survey results of no difference in the prevalence of bipolar disorder call into question reports of a protective effect of pregnancy on bipolar disorder.5

A recent study in Denmark also found no differences in first-time psychiatric episodes treated at outpatient facilities but did find a significant increase in first-time psychiatric episodes treated at inpatient facilities shortly following childbirth when compared with during pregnancy, suggesting a potentially different etiology for severe mental health disorders. The authors suggest that childbirth could serve as a "potent and highly significant trigger" of severe psychiatric episodes.6

Among perinatal mental health disorder, depression is the most common form, although depression and anxiety often coexist. In women with postpartum depression, for example, 66 percent have been reported to have a comorbid anxiety disorder diagnosis.7

Untreated maternal psychiatric disorders can have devasting sequelae. Pregnancy-associated suicide kills more women than hemorrhage or preeclampsia,8 underscoring the importance of screening and treatment for perinatal mood disorders. Moreover, depressive symptoms are associated with adverse parenting practices, including reduced use of safety and child development practices and increased harsh punishment9 including suicidal ideation and/or fears of hurting the newborn. In addition, postpartum depression is associated with reduced maternal sensitivity,10 which may adversely affect development of infant emotional regulation and attachment.11,12 Insecure attachment, in turn, increases risk of psychiatric disease in the child.10,13 Given the harm to both mother and child associated with untreated perinatal mood disorders, the U.S. Preventative Health Task Force14 and the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology15 recommend universal screening for perinatal depression.

With increased recognition of the consequences of perinatal psychiatric disorders, information about the efficacy and side effects of treatments is needed to inform clinical decisionmaking. Treatment choices include pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, and other approaches (e.g., yoga, mindfulness, self-care, nutritional or herbal supplements). The likelihood of perinatal exposure to psychotropic drugs is high and increasing. Medicaid claims data from 2000 to 2007 show that 8.1 percent of women were exposed to an antidepressant during pregnancy.16 More recent data (2006 to 2011) of women with private insurance indicate a rate of exposure of 10.1 percent to psychotropic medications during pregnancy.17 Among women of childbearing age, use of prescription antidepressants has increased markedly over the past 30 years. From 1988 to 1994, 2.3 percent had used a prescription antidepressant in the 30 days prior to the survey; from 2007 to 2010, the rate increased to 14.8 percent.18 Use of other psychotropic medications during pregnancy has similarly increased. From 2001 to 2007, use of atypical antipsychotics by pregnant women more than doubled, from 0.3 percent to 0.8 percent;19 use of antiepileptic drugs increased from 1.57 percent of deliveries to 2.19 percent.20 Currently no drugs target postpartum depression specifically, although a new drug, brexanolone, is in the FDA approval pipeline. Rates of exposure in the perinatal period will likely increase: newer pharmacologic compounds, some targeting postpartum depression specifically, are being tested in the perinatal population.21,22 Nonetheless, uncertainty persists on crucial questions about how to safely manage medications during the pregnancy and postpartum phases.

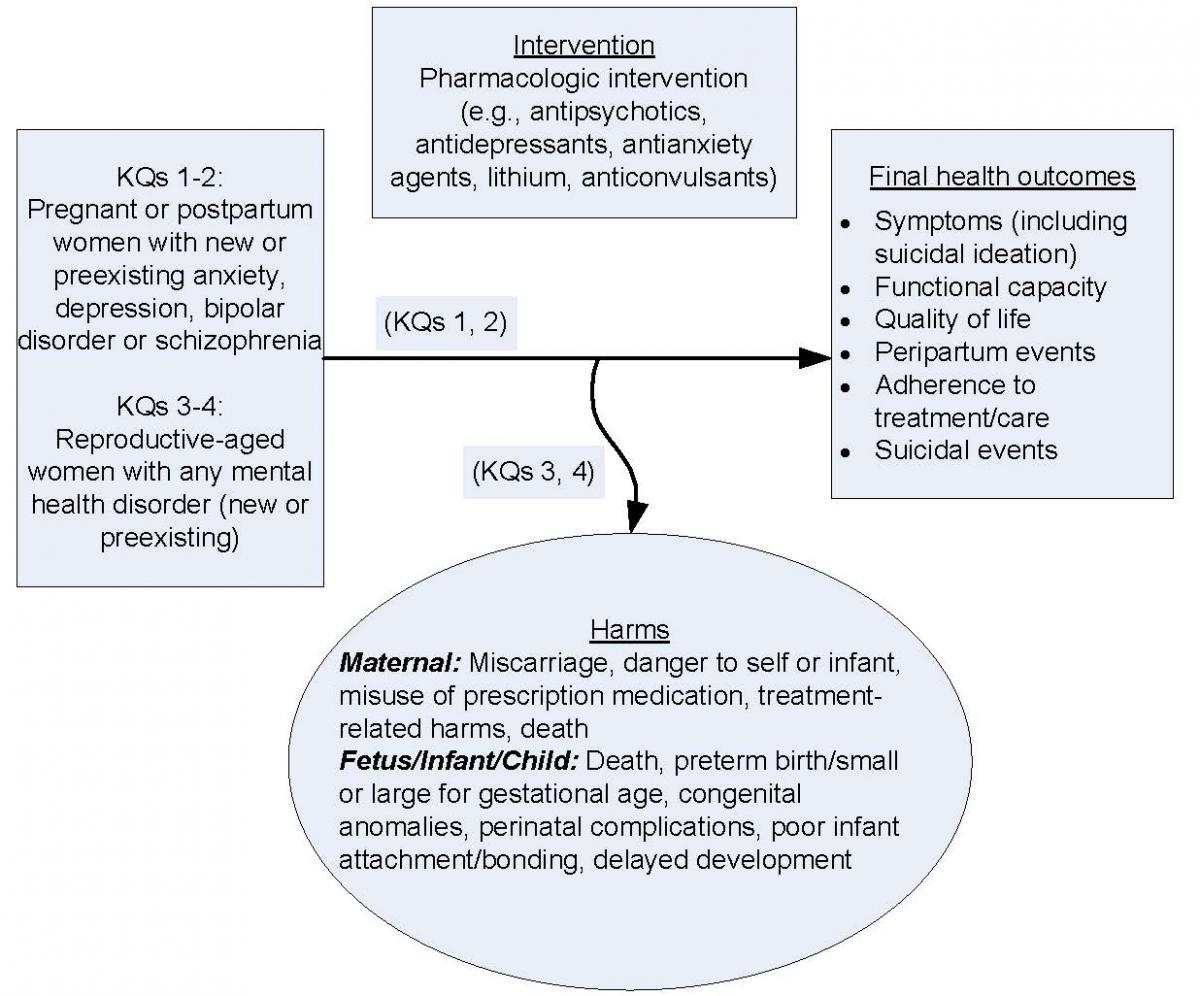

For women who cannot rely on nonpharmacological approaches alone, a critical question is whether the net benefit (the balance between harms and benefits) for mother and fetus of treating psychiatric disease with pharmacologic interventions outweighs their net harms. Similarly, a key decision for breastfeeding women is whether the net harm of infants' medication exposure via breastmilk outweighs either harms to women of not being treated with pharmacotherapy11,23-25 or harms to infants of not being breastfed.26 The review, as currently scoped, attempts to address these vital questions. KQs 1 and 2 evaluate benefits and comparative benefits of pharmacologic interventions in pregnant or breastfeeding women with an anxiety, depressive, bipolar disorder or schizophrenia. Key Questions (KQs) 3 and 4 focus on maternal and fetal harms and comparative harms of pharmacologic interventions in women with any mental health condition during the preconception, pregnancy, or postpartum phase. A Contextual Question (CQ) asks about the harms of not treating a disorder or stopping or switching medications. This review, as framed, does not span all eligible interventions. Notably, the review does not address the efficacy of psychological interventions (i.e., psychological interventions vs. usual care, wait-list, or no treatment). Although this exclusion limits the scope of the review, it reduces the heterogeneity of the included populations: the efficacy population for psychotherapy-only interventions may have lower severity of illness.

This literature has two important challenges: lack of trial data leading to reliance on observational data and heterogeneity of the included conditions, medications, and comparators. Concerns about maternal and fetal safety, ethics, and the logistics of trial design have led to a dearth of randomized controlled trials to inform clinical decisionmaking.27 Trial evidence on psychotropic medications in pregnant or breastfeeding women is "historically lacking" for any indication.28 High-quality safety data are also limited.29 Absent high-quality evidence, clinical recommendations may vary on key decisions—such as whether to continue antidepressants in the preconception, pregnancy, and breastfeeding phases and what agent to use30 or rely on expert opinion.31,32

Study designs most likely to report on harms associated with maternal use of psychotropic medications include case-control studies, pregnancy registry studies, observational cohort studies, and secondary analyses of administrative databases. Each of these study designs has strengths and limitations. Case-control studies allow assessment of associations with rare outcomes, such as congenital anomalies; however, both recall bias and selection of an appropriate control population are concerns. Pregnancy registry studies facilitate postmarketing surveillance of new medications but may be limited by selection bias. Observational cohort studies, particularly large birth cohorts such as the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study33 and the Danish National Birth Cohort,34 capture sufficiently large samples to assess relatively rare outcomes with prospective assessment of exposure. However, confounding by indication and underlying disease severity remain concerns. Large administrative databases35,36 allow assessment of rare outcomes such as congenital anomalies but have problems in identifying pregnancies; misclassifying exposures; specifying outcomes and covariates; and addressing confounding, comparison cohorts, and statistical testing.36

All observational studies are subject to confounding by indication—that is, the extent to which exposure to maternal mental health morbidity influences both exposure to the medication and outcomes. To address this limitation, some studies have compared women receiving pharmacotherapy with women who have the same mental health disorder but who are not receiving treatment.37 However, this approach does not entirely address confounding by indication, in that women who are receiving pharmacologic treatment may be likely to have more severe underlying disease than women who forgo pharmacologic therapy. Others trying to address residual confounding with high-dimensional propensity scores have found that full adjustment leads to many associations being no longer statistically significant.38,39

The heterogeneity of included populations and pharmacologic interventions adds further complexity to interpreting the evidence. Some medications are prescribed across numerous conditions, and coexisting mental health conditions are common. At the same time, complexity and severity of mental health conditions, baseline symptom control, and health status also require consideration. For example, an augmenting dose for an atypical antipsychotic in hard-to-treat major depression is much lower than a dose used to treat a primary bipolar disorder; the balance of benefits and harms would differ as a result. Underlying variations in population characteristics and medication dosing might explain important differences in harms.

The heterogeneity of interventions also introduces complexity. A woman's decision to pursue pharmacologic or psychological therapy may turn on socioeconomic factors such as locally available psychotherapists, insurance coverage, transportation, paid time off from work to attend therapy, and access to child care. These social determinants of health may confound observed associations between nonuse of pharmacologic therapy and clinical outcomes.

Rationale for the Review

Given the prevalence of pharmacologic interventions in pregnancy, uncertainties in the evidence base, and variations in clinical practice and guidelines, a careful review of the evidence is critical for patients and clinicians to make informed decisions about risks and benefits.

II. The Key Questions

The KQs were posted for public comment July 9 through July 31, 2018. The original KQs for benefits (KQ 3 and KQ 4) included substance use disorders. The revised KQs no longer include substance use disorders; they now include schizophrenia. The revision will help bring better focus to the report and make the scope more manageable.

Key Question 1: Among pregnant and postpartum women, what is the effectiveness of pharmacologic interventions on maternal outcomes

- Among those with a new or preexisting anxiety disorder?

- Among those with a new or preexisting depressive disorder?

- Among those with a new or preexisting bipolar disorder?

- Among those with new or preexisting schizophrenia?

Key Question 2: Among pregnant and postpartum women, what is the comparative effectiveness of pharmacologic interventions on maternal outcomes

- Among those with a new or preexisting anxiety disorder?

- Among those with a new or preexisting depressive disorder?

- Among those with a new or preexisting bipolar disorder?

- Among those with new or preexisting schizophrenia?

Key Question 3: Among reproductive-aged women with any mental health disorder, what are the maternal and fetal harms associated with pharmacologic interventions for a mental health disorder during preconception, pregnancy, and postpartum?

Key Question 4: Among reproductive-aged women with any mental health disorder, what are the comparative maternal and fetal harms of pharmacologic interventions for a mental health disorder during preconception, pregnancy, and postpartum?

Contextual Question 1: Among women who are preconceptional, pregnant, or postpartum, within a given disorder, what are the harms of NOT treating or stopping a pharmacological treatment, or of switching medications?

III. Analytic Framework

IV. Methods

Table 1. Inclusion/exclusion table

| PICOTS | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|

Population |

KQ 1, KQ 2: Women who are pregnant or postpartum with new or preexisting diagnosis of anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia

KQ 3, KQ 4: Reproductive-aged women (15-44 years old during preconception [≤12 weeks before pregnancy], pregnancy, and postpartum [through 1 year]) with any mental health disorder (new or preexisting) |

KQs 1, 2: Studies of women with disorders other than anxiety (including PTSD and OCD), depression, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia KQs 3, 4: <90% of reproductive age (15-44) KQs 1-4: Studies with 100% substance use disorders |

|

Intervention† |

Pharmacologic interventions for a mental health disorder including:

|

All other interventions |

|

Comparator |

KQ 1, KQ 3: Placebo or no treatment KQ 2, KQ 4: Other pharmacologic interventions, any psychotherapy, combined pharmacotherapy, and psychotherapy |

KQ 1, KQ 3: Active comparators, no comparators KQ 2, KQ 4:

|

|

Outcomes‡ |

KQ 1, KQ 2: Effectiveness

Suicidal events KQ 3, KQ 4: Harms

|

All other outcomes |

|

Time frame |

Followup KQ 1, KQ 2: From conception up to 1 year postpartum for maternal outcomes KQ 3, KQ 4: All |

Followup

|

|

Settings§ |

Clinical setting All settings |

Clinical setting None |

|

Study design |

|

All other designs and studies using included designs that do not meet the sample size criterion |

|

Language |

Studies published in English |

Studies published in languages other than English |

* We will limit include outcomes to those using validated measures. Another potential exclusions, depending on volume of yield, include studies that fail to control for confounding.

† Drugs such as brexanolone that are awaiting FDA approval will be included in the review in the review once they are approved

‡We will focus strength of evidence (SOE) grades on outcomes prioritized by the Technical Expert Panel (TEP).

§ Depending on volume, we may limit the primary analysis to studies from geographic settings with resources comparable or applicable to the United States

Literature Search Strategies

We will systematically search, review, and analyze the scientific evidence for each KQ. To identify articles relevant to each KQ, we will begin with a focused MEDLINE search using a variety of terms, medical subject headings (MeSH), and major headings and will limit the search to English-language and human-only studies. We will not restrict the search by publication date.

We list relevant terms to include in Appendix A. To cover our target population, and medications relevant to pharmacotherapy for the included mental health conditions in the review, we will also search the Cochrane Library, the Cochrane Central Trials Registry, PsycINFO, and EMBASE. We will conduct quality checks to ensure our search identifies known studies. If not, we will revise and rerun our searches. An experienced librarian familiar with systematic reviews will design and conduct all searches in consultation with the review team. We will search the gray literature for unpublished studies relevant to this review and will include studies that meet all the inclusion criteria and contain enough methodological information for assessing internal validity/quality. Sources of gray literature include ClinicalTrials.gov, the World Health Organization's International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP), pharmaceutical companies' dossiers (for pharmacotherapies of interest), and scientific evidence and, if applicable, data received in response to Federal Register notice requests.

We will also conduct an updated literature search (of the same databases searched initially) concurrent with the draft report peer/public review process. We will investigate any literature the peer reviewers or the public suggest and, if appropriate, will incorporate them into the final review.

Study Selection

Two trained research team members will independently review all titles and abstracts identified through searches for eligibility against our inclusion/exclusion criteria using Abstrackr.40 Studies marked for possible inclusion by either reviewer will undergo a full-text review. For studies without adequate information to determine inclusion or exclusion, we will retrieve the full text and then make the determination. All results will be tracked in an EndNote® bibliographic database (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY).

We will retrieve and review the full text of all titles included during the title/abstract review phase and through hand searches. Two trained team members will independently review each full-text article for inclusion or exclusion based on the eligibility criteria described above. If both reviewers agree that a study does not meet the eligibility criteria, the study will be excluded. If the reviewers disagree, conflicts will be resolved by discussion and consensus or by consulting a third member of the review team. As described above, all results will be tracked in an EndNote database. We will record the reason why each excluded full text did not satisfy the eligibility criteria so that we can later compile a comprehensive list of such studies.

Data Abstraction and Data Management

We will compile a list of studies that accounts for all eligible companion articles to avoid duplication. For studies that meet our inclusion criteria, we will abstract relevant information into a table displaying study characteristics. We will design data abstraction forms to gather pertinent information from each article, including characteristics of study populations, settings, interventions, comparators, study designs, methods, and results. Trained reviewers will extract the relevant data from each included article into the evidence tables. A second member of the team will review all data abstractions for completeness and accuracy. Data abstraction templates and tables will be included in the appendix of the report.

Assessment of Methodological Risk of Bias of Individual Studies.

We will use the criteria set forth by the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research's (AHRQ's) Methods Guide for Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. To assess the risk of bias (i.e., internal validity), we will use the ROBINS-141 tool for observational studies and the Cochrane randomized controlled trial (RCT) tool42 for RCTs (if we find any eligible trials). For both RCTs and observational studies, risk of bias assessment will include questions to assess selection bias, confounding, performance bias, detection bias, and attrition bias; concepts covered include those about adequacy of randomization (for RCTs only), similarity of groups at baseline, masking, attrition, whether intention-to-treat analysis was used, method of handling dropouts and missing data, validity and reliability of outcome measures, and treatment fidelity.43

Two independent reviewers will assign risk of bias ratings for outcomes from each study but will also specify when the risk of bias for an individual outcome may be lower than the rating for the study overall. Disagreements between the two reviewers will be resolved by discussion and consensus or by consulting a third member of the team. We will give a low risk of bias rating for outcomes that meet all criteria. Studies that do not report their methods sufficiently may be rated as unclear risk of bias. We will give a high risk of bias rating to outcomes from studies that have a methodological shortcoming in one or more categories and will exclude them from our main analyses.

Data Synthesis

We will summarize all included studies in narrative form and in summary tables that tabulate the important features of the study populations, design, intervention, outcomes, setting (including geographic location), and results. Besides mention of basic study characteristics, we will include only findings from studies of low, medium, or unclear risk of bias in our main report, synthesized either qualitatively or quantitatively as permitted. Findings from studies determined to be of high risk of bias will be listed in the evidence tables in the appendix. If feasible, qualitative or quantitative sensitivity analyses may be conducted to gauge the difference in conclusions upon including and excluding high risk of bias studies.

If we find three or more studies for a comparison of an outcome of interest, we will consider pooling our findings by using quantitative analysis (i.e., meta-analysis) of the data from those studies. We will also consider conducting network meta-analysis using Bayesian methods to compare the interventions with each other if we identify at least three studies that tested the same intervention with a common comparator (e.g., placebo). For all analyses, we will use random effects models to estimate pooled or comparative effects; unlike a fixed-effects model, this approach allows for the likelihood that the true population effect may vary from study to study. To determine whether quantitative analyses are appropriate, we will assess the clinical and methodological heterogeneity of the studies under consideration following established guidance.44

If we conduct quantitative syntheses (i.e., meta-analysis), we will assess statistical heterogeneity in effects between studies by calculating the chi-squared statistic and the I2 statistic (the proportion of variation in study estimates due to heterogeneity). The importance of the observed value of I2 depends on the magnitude and direction of effects and on the strength of evidence (SOE) for heterogeneity (e.g., p-value from the chi-squared test or a confidence interval for I2). If we include any meta-analyses with considerable statistical heterogeneity in this report, we will provide an explanation for doing so, considering the magnitude and direction of effects.

When possible, for each intervention/comparator grouping, we will present findings clustered by disorder and medication. For benefits, the results will be sorted by disorder first, in keeping with the KQs. For harms, we may elect to summarize studies by both medication and disorder, depending on the volume of evidence and the specificity of the data on adverse events. We anticipate that at least some registry studies may present results by medication and may not always stratify results by disorder.

In addition, to examine potential sources of heterogeneity, we will use meta-regression or subgroup analyses to examine effect sizes by level of severity and comorbidity, patient characteristics (e.g., gender of the child for child outcomes, race/ethnicity, region of residence), and intervention characteristics (mode of delivery, including technology-based delivery) as permitted by the number of studies that have similar interventions, comparators, outcomes, and timing of assessments. When quantitative analyses are not appropriate (e.g., due to heterogeneity, insufficient numbers of similar studies, or insufficiency or variation in outcome reporting), we will synthesize the data qualitatively.

Grading the Strength of Evidence for Major Comparisons and Outcomes

We will grade the SOE based on the guidance established for the Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) Program.45 Developed to grade the overall strength of a body of evidence, this approach incorporates five key domains: risk of bias (includes study design and aggregate quality), consistency, directness, precision of the evidence, and reporting bias. It also considers other optional domains that may be relevant for some scenarios, such as a dose-response association, plausible confounding that would decrease the observed effect, and strength of association (magnitude of effect).

Table 2 describes the grades of evidence that can be assigned. Grades reflect the strength of the body of evidence to answer KQs on the comparative effectiveness, efficacy, and harms of the interventions included in this review. Two reviewers will assess each domain for each key outcome, and differences will be resolved by consensus. If the volume of evidence is large, we may focus the SOE for the outcomes deemed to be of greatest importance to decisionmakers and those most commonly reported in the literature.

Table 2. Definitions of the grades of overall SOE46

|

Grade |

Definition |

|---|---|

|

High |

High confidence that the evidence reflects the true effect. Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. |

|

Moderate |

Moderate confidence that the evidence reflects the true effect. Further research may change our confidence in the estimate of the effect and may change the estimate. |

|

Low |

Low confidence that the evidence reflects the true effect. Further research is likely to change our confidence in the estimate of the effect and is likely to change the estimate. |

|

Insufficient |

Evidence either is unavailable or does not permit estimation of an effect. |

SOE = strength of evidence.

Assessing Applicability

We will assess the applicability of individual studies as well as the applicability of a body of evidence following guidance from the Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews.47 For individual studies, we will examine conditions that may limit applicability based on the PICOTS structure. Some factors identified a priori that may limit the applicability of evidence include the following: severity or type of disorder, comorbid physical or mental health conditions, age of the sample, use of multiple medications, setting of intervention, and participation in other types of treatment (e.g., psychotherapy).

V. References

- Pew Research Center. They're waiting longer, but U.S. women today more likely to have children than a decade ago. 2018.

- Vesga-Lopez O, Blanco C, Keyes K, et al. Psychiatric disorders in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008 Jul;65(7):805-15. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.805. PMID: 18606953.

- Howard LM, Molyneaux E, Dennis CL, et al. Non-psychotic mental disorders in the perinatal period. Lancet. 2014 Nov 15;384(9956):1775-88. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61276-9. PMID: 25455248.

- O'Hara MW, Wisner KL. Perinatal mental illness: definition, description and aetiology. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2014 Jan;28(1):3-12. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2013.09.002. PMID: 24140480.

- Grof P, Robbins W, Alda M, et al. Protective effect of pregnancy in women with lithium-responsive bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2000 Dec;61(1-2):31-9. PMID: 11099738.

- Munk-Olsen T, Maegbaek ML, Johannsen BM, et al. Perinatal psychiatric episodes: a population-based study on treatment incidence and prevalence. Transl Psychiatry. 2016 Oct 18;6(10):e919. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.190. PMID: 27754485.

- Wisner KL, Sit DK, McShea MC, et al. Onset timing, thoughts of self-harm, and diagnoses in postpartum women with screen-positive depression findings. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013 May;70(5):490-8. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.87. PMID: 23487258.

- Palladino CL, Singh V, Campbell J, et al. Homicide and suicide during the perinatal period: findings from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Nov;118(5):1056-63. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823294da. PMID: 22015873.

- McLearn KT, Minkovitz CS, Strobino DM, et al. The timing of maternal depressive symptoms and mothers' parenting practices with young children: implications for pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2006 Jul;118(1):e174-82. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1551. PMID: 16818531.

- Burke L. The impact of maternal depression on familial relationships. International Review of Psychiatry. 2003;15(3):243-55. doi: 10.1080/0954026031000136866. PMID: 2003-99739-005. First Author & Affiliation: Burke, L.

- Ashman SB, Dawson G. Maternal depression, infant psychobiological development, and risk for depression. In: Goodman SH, Gotlib IH, eds. Children of depressed parents. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002.

- Field T, Sandberg D, Garcia R, et al. Pregnancy problems, postpartum depression, and early mother/infant interactions. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21(6):1152-6. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.21.6.1152. PMID: 1986-09238-001. First Author & Affiliation: Field, Tiffany.

- Beck CT. The effects of postpartum depression on maternal-infant interaction: A meta-analysis. Nursing Research. 1995;44(5):298-304. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199509000-00007. PMID: 1996-14507-001. First Author & Affiliation: Beck, Cheryl Tatano.

- O'Connor E, Rossom RC, Henninger M, et al. Primary care screening for and treatment of depression in pregnant and postpartum women: evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016 Jan 26;315(4):388-406. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18948. PMID: 26813212.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 757. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2018. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Obstetric-Practice/Screening-for-Perinatal-Depression. Accessed on December 5 2018.

- Huybrechts KF, Palmsten K, Mogun H, et al. National trends in antidepressant medication treatment among publicly insured pregnant women. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013 May-Jun;35(3):265-71. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.12.010. PMID: 23374897.

- Hanley GE, Mintzes B. Patterns of psychotropic medicine use in pregnancy in the United States from 2006 to 2011 among women with private insurance. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014 Jul 22;14:242. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-14-242. PMID: 25048574.

- National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2013. In brief. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2014.

- Toh S, Li Q, Cheetham TC, et al. Prevalence and trends in the use of antipsychotic medications during pregnancy in the U.S., 2001-2007: a population-based study of 585,615 deliveries. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2013 Apr;16(2):149-57. doi: 10.1007/s00737-013-0330-6. PMID: 23389622.

- Bobo WV, Davis RL, Toh S, et al. Trends in the use of antiepileptic drugs among pregnant women in the US, 2001-2007: a medication exposure in pregnancy risk evaluation program study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2012 Nov;26(6):578-88. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12004. PMID: 23061694.

- Kanes S, Colquhoun H, Gunduz-Bruce H, et al. Brexanolone (SAGE-547 injection) in post-partum depression: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2017 Jul 29;390(10093):480-9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31264-3. PMID: 28619476.

- Kanes SJ, Colquhoun H, Doherty J, et al. Open-label, proof-of-concept study of brexanolone in the treatment of severe postpartum depression. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2017 Mar;32(2). doi: 10.1002/hup.2576. PMID: 28370307.

- Field T, Sandberg D, Garcia R, et al. Pregnancy problems, postpartum depression, and early mother‚ infant interactions. Dev Psychol. 1985;21(6):1152-6. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.21.6.1152.

- Brand SR, Brennan PA. Impact of antenatal and postpartum maternal mental illness: how are the children? Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Sep;52(3):441-55. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181b52930. PMID: 19661760.

- Grace LS, Evindar A, Stewart ED. The effect of postpartum depression on child cognitive development and behavior: a review and critical analysis of the literature. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2003;6(4):263-74. doi: 10.1007/s00737-003-0024-6.

- Bartick MC, Schwarz EB, Green BD, et al. Suboptimal breastfeeding in the United States: maternal and pediatric health outcomes and costs. Matern Child Nutr. 2017 Jan;13(1):1-13. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12366. PMID: 27647492.

- Sheffield JS, Siegel D, Mirochnick M, et al. Designing drug trials: considerations for pregnant women. Clin Infect Dis. 2014 Dec 15;59 Suppl 7:S437-44. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu709. PMID: 25425722.

- Gee RE, Wood SF, Schubert KG. Women's health, pregnancy, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Jan;123(1):161-5. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000063. PMID: 24463677.

- Thorpe PG, Gilboa SM, Hernandez-Diaz S, et al. Medications in the first trimester of pregnancy: most common exposures and critical gaps in understanding fetal risk. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013 Sep;22(9):1013-8. doi: 10.1002/pds.3495. PMID: 23893932.

- Molenaar NM, Kamperman AM, Boyce P, et al. Guidelines on treatment of perinatal depression with antidepressants: an international review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2018 Apr;52(4):320-7. doi: 10.1177/0004867418762057. PMID: 29506399.

- Koren G, Nordeng H. Antidepressant use during pregnancy: the benefit-risk ratio. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Feb 21. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.02.009. PMID: 22425404.

- Muzik M, Hamilton SE. Use of antidepressants during pregnancy?: what to consider when weighing treatment with antidepressants against untreated depression. Matern Child Health J. 2016 Nov;20(11):2268-79. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-2038-5. PMID: 27461022.

- Lupattelli A, Wood M, Ystrom E, et al. Effect of time-dependent selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants during pregnancy on behavioral, emotional, and social development in preschool-aged children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018 Mar;57(3):200-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.12.010. PMID: 29496129.

- Grzeskowiak LE, Gilbert AL, Sorensen TI, et al. Prenatal exposure to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and childhood overweight at 7 years of age. Ann Epidemiol. 2013 Nov;23(11):681-7. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.08.005. PMID: 24113367.

- Palmsten K, Huybrechts KF, Mogun H, et al. Harnessing the Medicaid Analytic eXtract (MAX) to evaluate medications in pregnancy: design considerations. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e67405. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067405. PMID: 23840692.

- Petersen I, McCrea RL, Sammon CJ, et al. Risks and benefits of psychotropic medication in pregnancy: cohort studies based on UK electronic primary care health records. Health Technol Assess. 2016 Mar;20(23):1-176. doi: 10.3310/hta20230. PMID: 27029490.

- Eke AC, Saccone G, Berghella V. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) use during pregnancy and risk of preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2016 Nov;123(12):1900-7. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.14144. PMID: 27239775.

- Huybrechts KF, Bateman BT, Palmsten K, et al. Antidepressant use late in pregnancy and risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. JAMA. 2015 Jun 2;313(21):2142-51. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.5605. PMID: 26034955.

- Huybrechts KF, Palmsten K, Avorn J, et al. Antidepressant use in pregnancy and the risk of cardiac defects. N Engl J Med. 2014 Jun 19;370(25):2397-407. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1312828. PMID: 24941178.

- Wallace BC, Small K, Brodley CE, et al. Deploying an interactive machine learning system in an evidence-based practice center: abstrackr. Proc. of the ACM International Health Informatics Symposium (IHI). 2012:819-24.

- Sterne JA, Hernan MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016 Oct 12;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. PMID: 27733354.

- Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. www.handbook.cochrane.org. Accessed on January 10 2017.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. AHRQ Publication No. 10(14)-EHC063-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; January 2014.

- West SL, Gartlehner G, Mansfield AJ, et al. Comparative Effectiveness Review Methods: Clinical Heterogeneity Methods Research Report. (Prepared by RTI International-University of North Carolina Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2007-10056-I). AHRQ Publication No: 10-EHC070-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; September 2010.

- Owens DK, Lohr KN, Atkins D, et al. AHRQ series paper 5: grading the strength of a body of evidence when comparing medical interventions--agency for healthcare research and quality and the effective health-care program. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010 May;63(5):513-23. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.03.009. PMID: 19595577.

- Berkman ND, Lohr KN, Ansari MT, et al. Grading the strength of a body of evidence when assessing health care interventions: an EPC update. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015 Nov;68(11):1312-24. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.11.023. PMID: 25721570.

- Atkins D, Chang SM, Gartlehner G, et al. Assessing applicability when comparing medical interventions: AHRQ and the Effective Health Care Program. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011 Nov;64(11):1198-207. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.11.021. PMID: 21463926.

VI. Definition of Terms

Not applicable.

VII. Summary of Protocol Amendments

If we need to amend this protocol, we will give the date of each amendment, describe the change and give the rationale in this section. Changes will not be incorporated into the protocol. Example table below:

Table 3. Title

|

Date |

Section |

Original Protocol |

Revised Protocol |

Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

This should be the effective date of the change in protocol |

Specify where the change would be found in the protocol |

Describe the language of the original protocol. |

Describe the change in protocol. |

Justify why the change will improve the report. If necessary, describe why the change does not introduce bias. Do not use justification as "because the AE/TOO/TEP/Peer reviewer told us to" but explain what the change hopes to accomplish. |

VIII. Review of Key Questions

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) posted the key questions on the AHRQ Effective Health Care Website for public comment. The Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) refined and finalized the key questions after review of the public comments, and input from Key Informants and the Technical Expert Panel (TEP). This input is intended to ensure that the key questions are specific and relevant.

IX. Key Informants

Key Informants are the end users of research, including patients and caregivers, practicing clinicians, relevant professional and consumer organizations, purchasers of health care, and others with experience in making health care decisions. Within the EPC program, the Key Informant role is to provide input into identifying the Key Questions for research that will inform healthcare decisions. The EPC solicits input from Key Informants when developing questions for systematic review or when identifying high priority research gaps and needed new research. Key Informants are not involved in analyzing the evidence or writing the report and have not reviewed the report, except as given the opportunity to do so through the peer or public review mechanism.

Key Informants must disclose any financial conflicts of interest greater than $5,000 and any other relevant business or professional conflicts of interest. Because of their role as end-users, individuals are invited to serve as Key Informants and those who present with potential conflicts may be retained. The AHRQ Task Order Officer (TOO) and the EPC work to balance, manage, or mitigate any potential conflicts of interest identified.

X. Technical Experts

Technical Experts constitute a multi-disciplinary group of clinical, content, and methodological experts who provide input in defining populations, interventions, comparisons, or outcomes and identify particular studies or databases to search. They are selected to provide broad expertise and perspectives specific to the topic under development. Divergent and conflicting opinions are common and perceived as healthy scientific discourse that results in a thoughtful, relevant systematic review. Therefore, study questions, design, and methodological approaches do not necessarily represent the views of individual technical and content experts. Technical Experts provide information to the EPC to identify literature search strategies and suggest approaches to specific issues as requested by the EPC. Technical Experts do not do analysis of any kind nor do they contribute to the writing of the report. They have not reviewed the report, except as given the opportunity to do so through the peer or public review mechanism.

Technical Experts must disclose any financial conflicts of interest greater than $5,000 and any other relevant business or professional conflicts of interest. Because of their unique clinical or content expertise, individuals are invited to serve as Technical Experts and those who present with potential conflicts may be retained. The AHRQ TOO and the EPC work to balance, manage, or mitigate any potential conflicts of interest identified.

XI. Peer Reviewers

Peer reviewers are invited to provide written comments on the draft report based on their clinical, content, or methodological expertise. The EPC considers all peer review comments on the draft report in preparation of the final report. Peer reviewers do not participate in writing or editing of the final report or other products. The final report does not necessarily represent the views of individual reviewers. The EPC will complete a disposition of all peer review comments. The disposition of comments for systematic reviews and technical briefs will be published three months after the publication of the evidence report.

Potential Peer Reviewers must disclose any financial conflicts of interest greater than $5,000 and any other relevant business or professional conflicts of interest. Invited Peer Reviewers may not have any financial conflict of interest greater than $5,000. Peer reviewers who disclose potential business or professional conflicts of interest may submit comments on draft reports through the public comment mechanism.

XII. EPC Team Disclosures

EPC core team members must disclose any financial conflicts of interest greater than $1,000 and any other relevant business or professional conflicts of interest. Related financial conflicts of interest that cumulatively total greater than $1,000 will usually disqualify EPC core team investigators.

XIII. Role of the Funder

This project was funded under Contract No. xxx-xxx from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The AHRQ Task Order Officer reviewed contract deliverables for adherence to contract requirements and quality. The authors of this report are responsible for its content. Statements in the report should not be construed as endorsement by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

XIV. Registration

This protocol will be registered in the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO).

Appendix A

|

Search |

Query |

Items Found |

|

Search ("Anxiety Disorders"[Mesh] OR anxiety[tiab] OR "Bipolar Disorder"[Mesh] OR bipolar[tiab] OR "Depressive Disorder"[MeSH] OR "Depressive Disorder, Major"[Mesh] OR Depression[Mesh] OR depress*[tiab] OR depression[tiab] OR depressive[tiab] OR depressed[tiab] OR "Dysthymic Disorder"[Mesh] OR dysthymia[tiab] OR dysthymic[tiab] OR "Feeding and Eating Disorders"[Mesh] OR anorexia[tiab] OR anorexic[tiab] OR "binge eating"[tiab] OR bulimic[tiab] OR bulimia[tiab] OR GAD OR "Psychotic Disorders"[Mesh] OR "psychotic disorder"[tiab] OR "psychotic disorders"[tiab] OR psychosis[tiab] OR psychoses[tiab] OR (mental[Tiab] AND (health[Tiab] OR illness[Tiab] OR disorders[Tiab])) OR "Mental Health"[Mesh] OR "Mental Disorders"[Mesh] OR "Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder"[Mesh] OR "Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder"[tiab] OR OCD[tiab] OR "panic disorder" OR "Persistent Depressive Disorder"[tiab] OR phobia*[tiab] OR phobic[tiab] OR psychotic*[tiab] OR "Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic"[Mesh] OR "post-traumatic stress disorder"[All Fields] OR "post-traumatic stress disorders"[All Fields] OR "posttraumatic stress disorder"[All Fields] OR "posttraumatic stress disorders"[All Fields] OR (disorder* AND "post-traumatic"[tiab]) OR "Stress Disorders, Traumatic"[Mesh:NOEXP] OR PTSD[tiab] OR "Schizophrenia"[Mesh] OR schizophren*[tiab] OR "stress disorder"[All Fields]) |

||

|

Search (alprazolam OR "Anti-Anxiety Agents"[Mesh] OR "Anti-Anxiety Agents"[Pharmacological Action] OR anti-anxiety OR antianxiety OR "Amitriptyline"[Mesh] OR amitriptyline OR "Amoxapine"[Mesh] OR amoxapine OR Anticonvulsants[Mesh] OR Anticonvulsants[Pharmacological Action] OR anticonvulsant OR anticonvulsants OR "Antidepressive Agents"[MeSH] OR "Antidepressive Agents, Second-Generation"[MeSH] OR anti-depress* OR antidepressant* OR antidepressive* OR "antidepressive agent" OR "antidepressive agents" OR "antidepressive drug" OR "antidepressive drugs" OR "Antipsychotic Agents"[Mesh] OR antipsychotic* OR anxiolytic* OR "Aripiprazole"[Mesh] OR aripiprazole OR "Asenapine"[Supplementary Concept] OR Asenapine OR benzodiazepine* OR brexanolone OR brexpiprazole OR Bupropion[MeSH] OR Bupropion OR "Buspirone"[Mesh] OR Buspirone OR "Carbamazepine"[Mesh] OR Carbamazepine OR Cariprazine OR "Chlorpromazine"[Mesh] OR Chlorpromazine OR Citalopram[MeSH] OR citalopram OR "clobazam" [Supplementary Concept] OR clobazam OR "Clomipramine"[Mesh] OR Clomipramine OR "Clonazepam"[Mesh] OR Clonazepam OR "Clonidine"[Mesh] OR Clonidine OR "Clorazepate Dipotassium"[Mesh] OR Clorazepate OR "Chlordiazepoxide"[Mesh] OR Chlordiazepoxide OR "Clozapine"[Mesh] OR clozapine) |

||

|

Search ("Desipramine"[Mesh] OR Desipramine OR "Desvenlafaxine Succinate"[Mesh] OR Desvenlafaxine OR "Diazepam"[Mesh] OR Diazepam OR "Diphenhydramine"[Mesh] OR Diphenhydramine OR "Doxepin"[Mesh] OR doxepin OR "Duloxetine Hydrochloride"[Mesh] OR duloxetine OR escitalopram OR "Eszopiclone"[Mesh] OR eszopiclone OR Fluoxetine[MeSH] OR fluoxetine OR "Fluphenazine"[Mesh] OR fluphenazine OR Fluvoxamine[MeSH] OR fluvoxamine OR "gabapentin"[Supplementary Concept] OR gabapentin OR "Haloperidol"[Mesh] OR Haloperidol OR "Hydroxyzine"[Mesh] OR Hydroxyzine OR "iloperidone"[Supplementary Concept] OR iloperidone OR "Imipramine"[Mesh] OR imipramine OR "lamotrigine"[Supplementary Concept] OR lamotrigine OR "Levomilnacipran"[Mesh] OR Levomilnacipran OR "Lisdexamfetamine Dimesylate "[Mesh] OR "Lithium Carbonate"[Mesh] OR lithium OR "Lorazepam"[Mesh] OR lorazepam OR "Lurasidone Hydrochloride"[Mesh] OR lurasidone OR "milnacipran"[Supplementary Concept]) |

||

|

Search (milnacipran OR "Maprotiline"[Mesh] OR Maprotiline OR mirtazapine[Supplementary Concept] OR mirtazapine OR "nefazodone"[Supplementary Concept] OR nefazodone OR "norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor" OR "norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors" OR "Nortriptyline"[Mesh] OR nortriptyline OR "olanzapine"[Supplementary Concept] OR olanzapine OR "oxcarbazepine"[Supplementary Concept] OR oxcarbazepine OR "Paliperidone Palmitate"[Mesh] OR Paliperidone OR Paroxetine[MeSH] OR paroxetine OR "Perphenazine"[Mesh] OR perphenazine OR "Protriptyline"[Mesh] OR protriptyline OR "Quetiapine Fumarate"[Mesh] OR quetiapine OR "ramelteon" [Supplementary Concept] OR ramelteon OR "Risperidone"[Mesh] OR risperidone OR "selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor" OR "selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors" OR "Serotonin Uptake Inhibitors"[MeSH] OR "serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor"[All Fields] OR "serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors"[All Fields] OR Sertraline[MeSH] OR sertraline OR SNRI* OR SSRI OR SSRIs) |

||

|

Search ("Temazepam"[Mesh] OR Temazepam "Thioridazine"[Mesh] OR Thioridazine OR "Thiothixene"[Mesh] OR Thiothixene OR "topiramate"[Supplementary Concept] OR topiramate OR Trazodone[Mesh] OR trazodone OR "Triazolam"[Mesh] OR triazolam OR "Trifluoperazine"[Mesh] OR Trifluoperazine OR "Trimipramine"[Mesh] OR Trimipramine OR "Valproic Acid"[Mesh] OR valproate OR "Venlafaxine Hydrochloride"[Mesh] OR venlafaxine OR "Vilazodone Hydrochloride"[Mesh] OR vilazodone OR "vortioxetine"[Supplementary Concept] OR vortioxetine OR "zaleplon"[Supplementary Concept] OR zaleplon OR "ziprasidone"[Supplementary Concept] OR ziprasidone OR "zolpidem"[Supplementary Concept] OR zolpidem) |

||

|

Search (#2 or #3 or #4 or #5) |

||

|

Search (#1 and #6) |

||

|

Search ("Pregnant Women"[Mesh] OR Pregnancy[Mesh] OR preconception[tiab] OR pregnant[tiab] OR pregnancy[tiab] OR prenatal[tiab] OR "post-partum"[tiab] OR postpartum[tiab] OR postnatal[tiab] OR perinatal[tiab] OR antenatal[tiab] OR "Maternal Health Services"[Mesh] OR "maternal health"[tiab] OR "Infant Nutritional Physiological Phenomena"[Mesh] OR "Breast Feeding"[Mesh] OR "breast feeding"[tiab] OR breastfeed*[tiab] OR (breast[tiab] AND fed[tiab]) OR breastfed[tiab] OR "Pregnancy Complications"[All Fields] OR "Maternal Welfare"[All Fields] OR gestation*[tiab] OR maternal*[tiab] OR "Pregnancy Outcome"[Mesh]) |

||

|

Search (#7 and #8) |

||

|

Search (#7 and #8) Filters: English |

||

|

Search ((#10 AND Humans[Mesh:noexp]) OR (#10 NOT Animals[Mesh:noexp])) |

||

|

Search (accident* OR "Adverse Effects" OR "adverse effect" or "adverse event" OR "adverse events" OR "adverse outcome" OR "adverse outcomes" OR "adverse reaction" OR "adverse reactions" OR "chemically induced" OR complication* OR death* OR "Drug Allergies" OR "Drug Dependency" OR "drug effects" OR "Drug Sensitivity" OR harm* OR harms OR "Long Term Adverse Effects"[Mesh] OR "manic episode" OR overdos* OR "Patient Safety" OR poisoning OR self damage* OR self injur* OR self inflict* OR "Self-Injurious Behavior"[Mesh] OR "Side Effect" OR "side effects" OR Suicide OR suicidal* OR toxicity) |

||

|

Search ("Abortion, Spontaneous"[Mesh] OR "Abruptio Placentae"[Mesh] OR abruption*[tiab] OR "Apgar Score"[Mesh] OR "Birth Weight/chemically induced"[Mesh] OR "Birth Weight/drug effects"[Mesh] OR "Child Development Disorders, Pervasive/chemically induced"[Mesh] OR "Child Development/drug effects"[Mesh] OR "Craniofacial Abnormalities/chemically induced"[Mesh] OR "Congenital Abnormalities"[Mesh] OR "congenital abnormality"[tiab] OR "congenital abnormalities"[tiab] OR death[tiab] OR "delayed development"[ALL FIELDS] OR "Glucose Intolerance"[Mesh] OR "glucose intolerance"[tiab] OR "Infant, Extremely Premature/growth and development"[Mesh] OR (infant* AND (attachment* OR bonding)) OR "Infertility, Female"[Mesh] OR "Infantile Respiratory Distress Syndrome"[tiab] OR infertility[tiab] OR ("Intellectual Disability"[Mesh] AND child*[tw]) OR "Low APGAR"[tiab] OR miscarry[tiab] OR miscarriage*[tiab] OR Mortality[Mesh] OR mortality[tiab] OR "Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome"[Mesh] OR "Neonatal Respiratory Distress Syndrome"[tiab] OR "Obstetric Labor, Premature"[Mesh] OR "Persistent Fetal Circulation Syndrome"[Mesh] OR "Persistent Pulmonary Hypertension of Newborn"[tiab] OR "Pre-Eclampsia"[Mesh] OR preeclampsia[tiab] OR pre-eclampsia[tiab] OR "Premature Birth"[Mesh] OR "premature birth"[tiab] OR "preterm birth" OR "pre-term birth"[tiab] OR "Prenatal Exposure Delayed Effects"[Mesh] OR "Prescription Drug Misuse"[Mesh] OR ("Prescription Drug"[tiab] AND misuse[tiab]) OR "preterm labor"[tiab] OR "pre-term labor"[tiab] OR "Postpartum Hemorrhage"[Mesh] OR "Respiratory Distress Syndrome, Newborn"[Mesh] OR "Uterine Inertia/chemically induced"[Mesh]) |

||

|

Search (#12 or #13) |

||

|

Search ("Drug Therapy"[Mesh] OR "drug therapy"[Subheading] OR drug*[tiab] OR pharmacotherap*[tiab] OR pharmacologic*[tiab] OR medicine*[tiab] OR medication*[tiab]) |

||

|

Search (#14 and #15 and #8 and #1) |

||

|

Search (#14 and #15 and #8 and #1) Filters: English |

||

|

Search ((#17 AND Humans[Mesh:noexp]) OR (#17 NOT Animals[Mesh:noexp])) |

||

|

Search ((#10 AND Humans[Mesh:noexp]) OR (#10 NOT Animals[Mesh:noexp])) Filters: Case Reports |

||

|

Search ((#10 AND Humans[Mesh:noexp]) OR (#10 NOT Animals[Mesh:noexp])) Filters: Case Reports; Editorial |

||

|

Search (#11 NOT (#19 or #20)) |

||

|

Search ((#17 AND Humans[Mesh:noexp]) OR (#17 NOT Animals[Mesh:noexp])) Filters: Case Reports |

||

|

Search ((#17 AND Humans[Mesh:noexp]) OR (#17 NOT Animals[Mesh:noexp])) Filters: Case Reports; Editorial |

||

|

Search (#18 NOT (#22 OR #23)) |

||

|

Search (#21 and #24) |

||

|

Search (#21 not #25) |

||

|

Search (#24 not #25) |

||

|

Search (#25 or #26 or #27) |