In childhood and adolescence, disruptive behaviors are a common reason for childhood referral to mental health services.1 Using the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health (N=43,283 children aged 3-17), the prevalence of current disruptive behaviors/conduct problems was 7.4% (compared with 7.1% for anxiety and 3.2% for depression).2 Included in this review are studies in children and adolescents formally diagnosed with a disruptive behavior disorder (DBD), such as oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), conduct disorder, and intermittent explosive disorder and studies in children and adolescents with clinically significant disruptive behavior who may not be formally diagnosed with a DBD.

The core features of DBDs are problems in self-control of emotions and behaviors that are often associated with violations of other’s rights and/or conflicts with societal norms or authority figures. To meet diagnostic criteria, these behaviors must cause impairments in the child’s or adolescent’s functioning at home, at school, or with peers. The cause(s) of disruptive behavior disorders in children and adolescents are not well understood but are likely often multi-factorial with risk factors including genetic, environmental and experiential factors such as parental psychopathology and/or substance use, low socioeconomic status, harsh discipline, and exposure to violence and ACEs (adverse childhood experiences), among others.3-6 Having multiple risk factors is associated with increased likelihood of DBDs.3,6,7 Individuals may also meet criteria for more than one mental health/neurodevelopmental disorder (e.g., 16%-20% of persons with conduct disorder also have comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD],8 and 90% of persons with oppositional defiant disorder will develop another mental health disorder in their lifetime9).

Some studies report disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of DBDs due to such factors as gender, race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status (SES), suggesting that diagnosis (and subsequent treatment) may be subject to observer bias. For example, several studies have found that Black children who exhibit disruptive behaviors are more likely to be diagnosed with oppositional defiant disorder than White children who engage in similar behaviors while White children are more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD than Black children.10-12 These differences in identifying children with a DBD or disruptive behaviors, which are observer and context dependent, disproportionately affect minority children; the diagnosis impacts the child’s treatment options and the child may also experience long-term consequences related to the negative associations with being diagnosed with a DBD as opposed to a less-stigmatized diagnosis (e.g., adjustment disorder, autism, ADHD).13 This review seeks to identify disparities in both diagnosis and treatment of DBDs.

Treatment of DBDs include psychosocial interventions (e.g., psychotherapy, psychosocial education) for the child and parents/caregivers or both, pharmacotherapy for the child (e.g., antipsychotics, stimulants) or a combination of psychosocial and pharmacological interventions. It is currently recommended that treatment for DBDs in childhood and adolescence be individualized. In 2015, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) published a comparative effectiveness review on psychosocial and pharmacologic interventions for disruptive behavior disorders in children and adolescents that included 84 studies and found that psychosocial interventions that include a component involving the parent are more effective than interventions that include only the child.14 Currently, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) is partnering with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to develop an updated systematic evidence review on Psychosocial and Pharmacologic Interventions for Disruptive Behavior in Children and Adolescents. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) intends to use the systematic evidence review to inform clinical practice guidance related to the topic. The present review is an update of AHRQ’s 2015 review to include more recently published evidence for psychosocial and pharmacological treatments for DBDs in order to guide clinical practice and provide the evidence base for guideline development.

Key decisional dilemmas for this review include determining the most effective treatments (while weighing benefits and harms) for DBDs and disruptive behaviors; determining if any child/adolescent characteristic, clinical characteristic, treatment characteristics or treatment history impact the benefits and harms of treatment; and assessing the presence and extent of disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of DBDs and their effect on psychosocial outcomes.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) posted the Key Questions on the AHRQ Effective Health Care Website for public comment from January 10, 2023 to January 31, 2023. We received 50 public comments from 11 individuals and organizations. Organizations commenting included the National Institute of Mental Health, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and the National Association of State Directors of Developmental Disabilities Services. In general, commenters expressed that the proposed key questions are important ones and were pleased at efforts to assess treatment effects by patient demographics and clinical characteristics, as well as by treatment characteristics and treatment history. Most comments involved requests to look at additional factors that may affect treatment success or to add additional outcomes. Based on public comments we clarified that intermittent explosive disorder is an included diagnosis in the PICOTS table (under population). We also reworded key questions 1-4 for clarity. We added LGBTQ+ status, English proficiency and health literacy to patient characteristics in key question 6a and added pubertal changes under age. For thoroughness, we added various conditions and characteristics to the key questions and PICOTS as recommended, with the understanding that important or meaningful conditions and characteristics will be included in the review whether they are specifically listed or not. We added autism spectrum disorder and comorbid internalizing disorders to clinical characteristics in key question 6b. We added examples of specific settings (e.g., group homes, residential treatment, family setting) to key question 6d. In response to public comments, we also adjusted the PICOTS table to include selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (atomoxetine) under pharmacologic interventions. We added age-inappropriate temper outburst to behavioral outcomes and fatigue to harms outcomes. One commenter recommended that we study treatments for disruptive behaviors in disruptive mood regulation disorder (DMDD), however treatments for a mood disorder alone are beyond the scope of this review. However, if a study enrolls children with conduct disorder and DMDD and the intervention targeted disruptive behaviors believed to be due to the conduct disorder, we would include the study. Another commenter recommended including complementary and integrative medicine strategies alone as treatment for DBD, which is also outside the scope of this review. However, if a study included yoga, for example, as part of a multicomponent treatment package that included a core included intervention such as psychotherapy, we would consider the study for inclusion. Similarly, we would consider including a study of occupational or other therapies as an adjunct treatment as long as the core treatment met inclusion criteria.

A technical expert panel (TEP) also reviewed the Key Questions, PICOTS inclusion and exclusion criteria, and our intended approach. We further modified the Key Questions and inclusion/exclusion criteria based on input with our ten TEP members (that included two federal partners). Changes to the protocol based on the TEP calls included the addition of socioeconomic status, health insurance status, use of oral contraceptives and rural versus urban to Key Question 6a patient characteristics, the addition of treatment satisfaction to behavioral outcomes, the addition of out-of-home placement and parenting stress to functional outcomes, and the addition of acne to harms outcomes.

Overall, public and TEP comments did not lead to a need for substantial changes to our intended approach.

Key Question 1. In children under 18 years of age diagnosed with disruptive behaviors, which psychosocial interventions are more effective for improving short-term and long-term psychosocial outcomes compared to no treatment or other psychosocial interventions?

Key Question 2. In children under 18 years of age diagnosed with disruptive behaviors, which pharmacologic interventions are more effective for improving short-term and long-term psychosocial outcomes compared to placebo or other pharmacologic interventions?

Key Question 3. In children under 18 years of age diagnosed with disruptive behaviors, what is the relative effectiveness of psychosocial interventions alone compared with pharmacologic interventions alone for improving short-term and long-term psychosocial outcomes?

Key Question 4. In children under 18 years of age diagnosed with disruptive behaviors, are combined psychosocial and pharmacologic interventions more effective for improving short-term and long-term psychosocial outcomes compared to either psychosocial or pharmacologic interventions alone?

Key Question 5. What are the harms associated with treating children under 18 years of age for disruptive behaviors with either psychosocial, pharmacologic or combined interventions?

Key Question 6:

Key Question 6a. Do interventions for disruptive behaviors vary in effectiveness and harms based on patient characteristics, including gender, age (including pubertal changes and use of oral contraceptives), racial/ethnic minority, LGBTQ+ status, English proficiency, health literacy, socioeconomic status, insurance status, rural versus urban, developmental status or delays, family history of disruptive behavior disorders or other mental health disorders, prenatal use of alcohol and drugs (specifically methamphetamine), history of trauma or Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), parental ACEs, access to social supports (neighborhood assets, family social support, worship community, etc.), personal and family beliefs about mental health (e.g. stigma around mental health), or other social determinants of health?

Key Question 6b. Do interventions for disruptive behaviors vary in effectiveness and harms based on clinical characteristics or manifestations of the disorder, including specific disruptive behavior (e.g., stealing, fighting) or specific disruptive behavior disorder (e.g., oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder), co-occurring behavioral disorders (e.g., attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder, internalizing disorders), related personality traits and symptom clusters, presence of non-behavioral comorbidities, age of onset, and duration?

Key Question 6c. Do interventions for disruptive behaviors vary in effectiveness and harms based on treatment history of the patient?

Key 6d. Do interventions for disruptive behaviors vary in effectiveness and harms based on characteristics of treatment, including setting (e.g., group homes, residential treatment, family setting), duration, delivery, timing, and dose?

Contextual Question 1. What are the disparities in the diagnosis of disruptive behavior disorders (based on characteristics such as gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, other social determinants of health, or other factors) in children and adolescents?

Contextual Question 2. What are the disparities in the treatment of disruptive behaviors or disruptive behavior disorders (based on characteristics such as gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, other social determinants of health, or other factors) in children and adolescents?

Contextual Question 3. How do disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of disruptive behaviors or disruptive behavior disorders affect behavioral and functional outcomes (e.g., compliance with teachers, contact with the juvenile justice system, substance abuse)?

PICOTS

Table 1 describes the populations, interventions, comparators, outcomes, timing, setting and study design criteria that will be used to screen studies.

Table 1. PICOTS: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

|

PICOTS |

Inclusion |

Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

|

Population |

KQs 1-6. Children under 18 years of age who are being treated for disruptive behavior or a disruptive behavior disorder that includes oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and intermittent explosive disorder; children with a co-occurring diagnosis (e.g., ADHD, ASD) provided the disruptive behavior treated is due to a DBD will be included |

|

|

Interventions |

KQs 1, 3-6. Psychosocial interventions for child, parents/family or both including:

KQs 2-6. Pharmacologic interventions that are FDA approved medications used on or off label, including the following class of drugs:

KQs 4-6. Combined psychosocial and pharmacologic interventions included for KQs 1-3. |

|

|

Comparators |

|

No comparison group, excluded interventions |

|

Outcomes |

KQs 1-4, 6. Behavioral outcomes:

KQs 1-4, 6. Functional outcomes:

KQ 5. Adverse effects/harms:

|

Unvalidated outcomes measures |

|

Timing |

KQs 1-6. Any length of follow-up |

|

|

Setting |

KQs 1-6. Clinical setting, including medical or psychosocial care that is delivered to individuals by clinical professionals (including telehealth), as well as individually focused programs to which clinicians refer their patients; may include classroom settings when intervention is directed to treat disruptive behavior(s) in a specific child (not the whole class) as part of that child’s treatment plan |

Exclude school wide or system wide settings (e.g., juvenile justice system) wherein interventions are targeted more widely |

|

Study Design |

Randomized controlled trials (no sample size limit), comparative nonrandomized controlled trials that adjust for confounding variables (N≥100), published in English on or after 1994. |

Published before 1994 |

Abbreviations: ADHD=Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; ASD=Autism Spectrum Disorder; DBD=Disruptive Behavior Disorders; FDA=U.S. Food and Drug Administration; KQ=Key Question

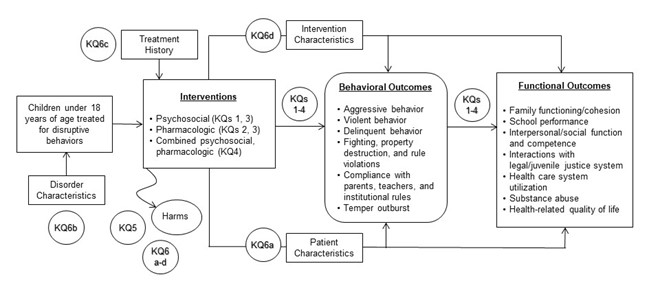

The analytic framework illustrates how the populations, interventions, and outcomes relate to the Key Questions (KQ) in the review.

Criteria for Inclusion/Exclusion of Studies in the Review:

We will use the inclusion/exclusion criteria described in the PICOTS to determine if a study qualifies for inclusion in our review. We will include studies in children diagnosed with a DBD or who are at or above the clinical threshold for DBD based on assessments using validated instruments, such as the State-Train Anger Expression Inventory. To be formally diagnosed with a DBD, the child must meet established criteria, such as that found in the DSM-5.15 To be diagnosed with a disruptive behavior for this review (in the absence of a formal diagnosis), the child must meet or exceed a clinical threshold for having disruptive behavior or a conduct problem using a validated clinical instrument (e.g., score ≥70th percentile on the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory). We will include treatment studies in children with a formal diagnosis of a DBD, as well as, studies in children exhibiting a disruptive behavior based on clinical thresholds, which is not secondary to another condition (e.g., autism, ADHD).

We will conduct sensitivity analyses to determine if the treatment effect is meaningfully different when studies in children with and without a formal diagnosis of a DBD are analyzed together versus when analyses are limited to studies in children who have a formal DBD diagnosis as defined in DSM-5.15 We will not include studies of children and adolescents who exhibit disruptive behaviors that are considered normal for their age (e.g., a study on how to manage a toddler’s temper tantrum or an 8-year-old’s bedtime resistance). To be eligible for inclusion, studies must report at least one included child outcome. Because children and adolescents may have multiple psychiatric diagnoses, in accordance with the 2015 AHRQ review,14 we will limit our review to studies that target disruptive behaviors and will exclude studies where the intervention targets a condition other than disruptive behaviors (e.g., a trial of stimulants in children targeting ADHD rather than oppositional defiant disorder). We will do this by examining the target behavior (e.g., stealing is more likely to be associated with ODD than ADHD) and the motivation behind the behavior (cannot sit still due to hyperactivity versus refusing to stay in seat in defiance of the teacher due to ODD). We will follow a best evidence approach16,17 and will focus on randomized trials where possible. When Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) evidence is lacking, we will consider comparative non-randomized studies of interventions (NRSI) that adjust for potential confounding factors (e.g., age, gender, co-occurring mental health conditions). We will consider NRSIs for harms when the study is designed specifically to assess harms.

Literature Search Strategies To Identify Relevant Studies to Answer the Key Questions:

The evidence base for this review will be identified primarily through searches of 4 databases: Ovid® MEDLINE®, the Cochrane Library, PsycINFO®, and Embase®. The search dates will be limited to a publication date of 2014 or later. For the primary search, we will concentrate on studies published since the end search dates for the 2015 AHRQ review. Additionally, the literature search now includes the terms “aggression” and “violence” as recommended by the key informants. Reference lists of included studies and relevant systematic reviews will be searched for includable literature. Appendix A contains our initial Ovid® MEDLINE® search strategy. We will conduct an updated MEDLINE® search at the same time we search the other databases. We will also review studies included in the prior review (1994 to 2014) for inclusion in this review. Citations will be screened using DistillerSR (DistillerSR. Version 2.35. DistillerSR Inc.; 2022.). For all studies, two reviewers will independently screen abstracts and full-text articles. Inclusion and exclusion conflicts will be resolved by discussion and consensus among team members. Included studies from the prior report will also be evaluated for inclusion in this review.

In order to address potential disparities related to DBDs, we will conduct an additional search for trials and other publications that may provide evidence of disparities in diagnosis and treatment of DBDs and the effect of these disparities on behavioral and functional outcomes.

Data Extraction and Data Management:

For all studies, a standardized template will be used. One reviewer will abstract study characteristics and findings and a second reviewer will spot check the data abstraction for accuracy. We will abstract participant psychiatric comorbidities. If possible, we will report treatment results based on psychiatric diagnoses at baseline for individual studies. If appropriate we will stratify results by co-occurring mental health conditions across studies. We will also abstract available participant characteristics (e.g., age, gender, race, family history, SES information, history of childhood trauma/violence, mood disorders), clinical characteristics (e.g., specific DBD or problem behaviors, age of onset, duration), treatment history (e.g., previous psychosocial and pharmacologic treatments, whether or not treatments are ongoing, treatment results), and characteristics of current treatment (e.g., treatment setting, provider type, duration of intervention, delivery of intervention, medication dose). If studies report results for multiple time points, we will abstract data for the various time points, and where possible, will highlight persistence of treatment effects beyond immediate post-treatment.

With thorough data abstraction, we may be able to stratify study results and/or conduct sensitivity analyses based on various characteristics to parse out how various participant, clinical, and treatment characteristics along with treatment history may differentially affect the magnitude of benefits and harms of interventions.

We will also report relevant evidence of disparities in diagnosis and treatment of DBDs and the effects on behavioral and functional outcomes and will present these findings under the Key Questions, Contextual Questions, background, discussion, and results sections of the review, as appropriate.

Assessment of Methodological Risk of Bias of Individual Studies:

We will use predefined criteria to assess risk of bias of included studies. Randomized controlled trials and NRSIs will be assessed using a priori established criteria consistent with the approach recommended in the chapter, Assessing the Risk of Bias of Individual Studies, described in the Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews.18,19 For RCTs, criteria will include factors such as methods of randomization, concealment of treatment allocation, details of blinding and analysis based on intention to treat. For NRSIs, criteria will include methods of patient selection (e.g., consecutive patients, use of an inception cohort) and appropriate control for confounding of relevant factors.20,21 We will downgrade studies that do not provide randomization, allocation, and/or blinding details, have a high rate of study loss to followup, or demonstrate selective reporting or other bias accordingly. To address the potential for publication bias, we will conduct appropriate statistical tests (e.g., funnel plots, statistical tests for Egger’s small sample effects) when we have sufficient (≥10) studies.22 These criteria and methods will be used in concordance with the approach recommended in the chapter, Assessing the Risk of Bias of Individual Studies When Comparing Medical Interventions,19 from the AHRQ Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews.18 Studies will be rated as being “low,” “moderate,” or “high” risk of bias as described below in Table 2. Each study will be dual reviewed for risk of bias by two team members. Disagreements in ratings will be resolved with discussion and consensus.

Table 2. Criteria for grading the risk of bias of individual studies

|

Rating |

Description and Criteria |

|---|---|

|

Low |

|

|

Moderate |

|

|

High |

|

Data Synthesis:

Evidence will be summarized qualitatively and quantitatively. We will consider classifying “short”, “intermediate”, and longer-term time frames and will analyze results across studies based on followup times, as appropriate. We will also stratify by preschool, school-age, and teenage children as appropriate, as treatments may differ and/or have different effects based on the age of the child. We will also stratify studies based on the target of the intervention (i.e., child alone, parent/caregiver alone, both child and parent/caregiver). When conducting meta-analyses, we will test for publication bias and for small study effects when there are sufficient data.23 We will attempt to explain important statistical heterogeneity present in pooled analyses through sensitivity analyses and stratification of studies based on factors likely to introduce heterogeneity (e.g., participant, clinical, and treatment characteristics, treatment history, other factors) as well as study quality and duration of treatment. The 2015 AHRQ review conducted a Bayesian network meta-analysis that included 28 studies. If we find sufficient new studies, we will update that network meta-analysis for efficacy. We do not anticipate being able to conduct a network meta-analysis on harms outcomes as it has been our experience that few trials of psychosocial interventions report harms. For all pooled analyses, we will estimate the magnitude of treatment effects as small, moderate, or large using the table 3 below as a guide as we have done in prior AHRQ reports. We will also report the magnitude of effect for individual studies when not pooled, as data permit.

Table 3. Definitions of effect sizes

|

Effect Size |

Definition |

|---|---|

|

Small effect |

|

|

Moderate effect |

|

|

Large effect |

|

MD = mean difference; OR = odds ratio; RR = relative risk; SMD = standardized mean difference

Grading the Strength of Evidence (SOE) for Major Comparisons and Outcomes:

Outcomes to be assessed for strength of evidence were prioritized based on input from the Technical Expert Panel (TEP) and team clinical experts. Based on this prioritized list, the strength of evidence for comparison-outcome pairs within each Key Question will be initially assessed by one researcher for each clinical outcome (see PICOTS) by using the approach described in the Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Review.18 To ensure consistency and validity of the evaluation, the initial assessment will be independently reviewed by at least one other experienced investigator using the following criteria:

- Study limitations (low, medium, or high level of study limitations)

- Consistency (consistent, inconsistent, or unknown/not applicable)

- Directness (direct or indirect)

- Precision (precise or imprecise)

- Reporting bias (suspected or undetected)

While additional outcomes will be reported, we will focus strength of evidence assessment on the following primary outcomes: The Eyberg Child Behavior Inventory (problem subscale, intensity subscale) and the Child Behavior Checklist (externalizing score) for psychosocial interventions and the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, the Overt Aggression Scale, and the Clinical Global Impressions scale for pharmacologic interventions. These outcomes are selected due to their prominence in the 2015 AHRQ review14 and to facilitate consistency in updating analyses and drawing conclusions across studies.

The strength of evidence will be assigned an overall grade of high, moderate, low, or insufficient according to a four-level scale (Table 4) by evaluating and weighing the combined results of the above domains.

Table 4. Description of the strength of evidence grades

|

Strength of Evidence |

Description |

|---|---|

|

High |

We are very confident that the estimate of effect lies close to the true effect for this outcome. The body of evidence has few or no deficiencies. We believe that the findings are stable, i.e., another study would not change the conclusions. |

|

Moderate |

We are moderately confident that the estimate of effect lies close to the true effect for this outcome. The body of evidence has some deficiencies. We believe that the findings are likely to be stable, but some doubt remains. |

|

Low |

We have limited confidence that the estimate of effect lies close to the true effect for this outcome. The body of evidence has major or numerous deficiencies (or both). We believe that additional evidence is needed before concluding either that the findings are stable or that the estimate of effect is close to the true effect. |

|

Insufficient |

We are unable to estimate an effect, or we have no confidence in the estimate of effect for this outcome. The body of evidence has unacceptable deficiencies which precludes reaching a firm conclusion. If no evidence is available, it will be noted as “no evidence.” |

The strength of the evidence may be downgraded based on the limitations described above. There are also situations where the observational evidence may be upgraded (e.g., large magnitude of effect, presence of dose-response relationship or existence of plausible unmeasured confounders), if there are no downgrades on the primary domains, as described in the AHRQ Methods Guide.18,19 Where both RCTs and nonrandomized studies of interventions (NRSIs) are included for a given intervention-outcome pair, we follow the additional guidance on weighting RCTs over NRSIs, assessing consistency across the two bodies of evidence, and determining a final rating.18

Summary tables will include ratings for individual strength of evidence domains (risk of bias, consistency, precision, directness) based on the totality of underlying evidence identified.

Assessing Applicability:

Applicability refers to the degree to which study participants are similar to real-world patients receiving care for disruptive behavior disorders. Applicability will be assessed in accordance with the AHRQ’s Methods Guide, using the PICOTS framework. If patient, clinical, and intervention characteristics are similar, then it is expected that outcomes associated with the intervention for study participants will likely be similar to outcomes in real-world patients. For example, exclusion of participants with psychiatric comorbidities reduces applicability to clinical practice since many children with DBDs have co-occurring psychiatric diagnoses and may respond differently to treatment than children without other mental health challenges. Multiple factors identified a priori that are likely to impact applicability include characteristics of enrolled patient populations (e.g., gender, age, race/ethnicity), clinical characteristics (e.g., specific DBD diagnosis or clinical threshold scores, severity of disease, age at diagnosis), intervention factors (e.g., setting, duration of treatment, treatment dose) and treatment history. Review of abstracted information on these factors will be used to assess situations for which the evidence is available and most relevant and to evaluate applicability to real-world clinical practice in typical U.S. settings. We will provide a qualitative summary of our assessment.

- Audit Commission for Local Authorities in England and Wales. Children in mind: Child and adolescent mental health services [briefing]: Audit Commission; 1999.

- Ghandour RM, Sherman LJ, Vladutiu CJ, et al. Prevalence and treatment of depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in us children. J Pediatr. 2019;206:256-67.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.09.021. PMID: 30322701.

- Gorman-Smith D. The social ecology of community and neighborhood and risk for antisocial behavior. Conduct and oppositional defiant disorders: epidemiology, risk factors, and treatment. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2003. p. 117-36.

- Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Rutter M, et al. The caregiving environments provided to children by depressed mothers with or without an antisocial history. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(6):1009-18. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1009. PMID: 16741201.

- Loeber R, Farrington DP. Young children who commit crime: Epidemiology, developmental origins, risk factors, early interventions, and policy implications. Dev Psychopathol. 2000;12(4):737-62. doi: 10.1017/s0954579400004107. PMID: 11202042.

- Youngstrom E, Weist MD, Albus KE. Exploring violence exposure, stress, protective factors and behavioral problems among inner-city youth. Am J Community Psychol. 2003;32(1-2):115-29. doi: 10.1023/a:1025607226122. PMID: 14570441.

- Sameroff A, Seifer R, McDonough SC. Contextual contributors to the assessment of infant mental health. Handbook of infant, toddler, and preschool mental health assessment.: Oxford University Press; 2004. p. 61-76.

- Lillig M. Conduct disorder: Recognition and management. Am Fam Physician. 2018;98(10):584-92. PMID: 30365289.

- Nock MK, Kazdin AE, Hiripi E, et al. Lifetime prevalence, correlates, and persistence of oppositional defiant disorder: results from the national comorbidity survey replication. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48(7):703-13. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01733.x. PMID: 17593151.

- Mak W, Rosenblatt A. Demographic influences on psychiatric diagnoses among youth served in california systems of care. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2002;11(2):165-78. doi: 10.1023/A:1015173508474.

- Mandell DS, Ittenbach RF, Levy SE, et al. Disparities in diagnoses received prior to a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37(9):1795-802. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0314-8. PMID: 17160456.

- Nguyen L, Huang LN, Arganza GF, et al. The influence of race and ethnicity on psychiatric diagnoses and clinical characteristics of children and adolescents in children's services. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2007;13(1):18-25. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.1.18. PMID: 17227173.

- Ballentine KL. Understanding racial differences in diagnosing odd versus adhd using critical race theory. Families in Society. 2019;100(3):282-92. doi: 10.1177/1044389419842765.

- Epstein R, Fonnesbeck C, Williamson E, Kuhn T, Lindegren ML, Rizzone K, Krishnaswami S, Sathe N, Ficzere CH, Ness GL, Wright GW, Raj M, Potter S, McPheeters M. Psychosocial and Pharmacologic Interventions for Disruptive Behavior in Children and Adolescents. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 154. (Prepared by the Vanderbilt Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-2012-00009-I.) AHRQ Publication No. 15(16)-EHC019-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; October 2015. www.effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/reports/final.cfm.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2014.

- Treadwell JR, Singh S, Talati R, et al. A Framework for "Best Evidence" Approaches in Systematic Reviews AHRQ Methods for Effective Health Care. (Prepared by the ECRI Institute Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. HHSA 290-2007-10063-I.) AHRQ Publication No. 11-EHC046-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011.

- Saldanha IJ, Skelly AC, Vander Ley K, Wang Z, Berliner E, Bass EB, Devine B, Hammarlund N, Adam GP, Duan-Porter D, Bañez LL, Jain A, Norris SL, Wilt TJ, Leas B, Siddique SM, Fiordalisi CV, Patino-Sutton C, Viswanathan M. Inclusion of Nonrandomized Studies of Interventions in Systematic Reviews of Intervention Effectiveness: An Update. Methods Guide for Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. (Prepared by the Scientific Resource Center under Contract No. 290-2017-00003-C.) AHRQ Publication No. 22-EHC033. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; September 2022. doi: 10.23970/AHRQEPCMETHODSGUIDENRSI. PMID: 36153934

- Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Content last reviewed April 2022. Rockville, MD: Effective Health Care Program, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; February 23, 2018. Chapters available at: https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/topics/cer-methodsguide/overview

- Viswanathan M, Patnode CD, Berkman ND, et al. Assessing the Risk of Bias in Systematic Reviews of Health Care Interventions. Methods Guide for Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. (Prepared by the Scientific Resource Center under Contract No. 290-2012-0004-C). AHRQ Publication No. 17(18)-EHC036- EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Dec 2017. Posted final reports are located on the Effective Health Care Program search page: https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/. doi: 10.23970/AHRQEPCMETHGUIDE2. PMID: 30125066

- Furlan AD, Malmivaara A, Chou R, et al. 2015 updated method guideline for systematic reviews in the cochrane back and neck group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015;40(21):1660-73. doi: 10.1097/brs.0000000000001061. PMID: 26208232.

- Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.2: John Wiley & Sons; 2021.

- Fu R, Gartlehner G, Grant M, et al. Conducting quantitative synthesis when comparing medical interventions: Ahrq and the effective health care program. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(11):1187-97. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.08.010. PMID: 21477993.

- Sterne JAC, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JPA, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d4002. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4002.

|

ACE |

Adverse Child Experience |

|---|---|

|

ADHD |

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder |

|

AHRQ |

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality |

|

DBD |

Disruptive Behavior Disorders |

|

DMDD |

Disruptive Mood Regulation Disorder |

|

DSM-5 |

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition |

|

EPC |

Evidence-based Practice Center |

|

FDA |

U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

|

KQ |

Key Question |

|

NRSI |

Non-Randomized Studies of Interventions |

|

ODD |

Oppositional Defiant Disorder |

|

PICOTS |

Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, Timing, and Setting |

|

RCT |

Randomized Controlled Trials |

|

SES |

Socioeconomic status |

|

TEP |

Technical Expert Panel |

|

TOO |

Task Order Officer |

None.

The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) posted the Key Questions on the AHRQ Effective Health Care Website for public comment from January 10, 2023 to January 31, 2023. The Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) refined and finalized them after reviewing of the public comments and seeking input from Key Informants and the Technical Expert Panel (TEP). This input is intended to ensure that the Key Questions are specific and relevant.

Key Informants are the end-users of research; they can include patients and caregivers, practicing clinicians, relevant professional and consumer organizations, purchasers of health care, and others with experience in making health care decisions. Within the EPC program, the Key Informant role is to provide input into the decisional dilemmas and help keep the focus on Key Questions that will inform health care decisions. The EPC solicits input from Key Informants when developing questions for the systematic review or when identifying high-priority research gaps and needed new research. Key Informants are not involved in analyzing the evidence or writing the report. They do not review the report, except as given the opportunity to do so through the peer or public review mechanism.

Key Informants must disclose any financial conflicts of interest greater than $5,000 and any other relevant business or professional conflicts of interest. Because of their role as end-users, individuals are invited to serve as Key Informants and those who present with potential conflicts may be retained. The AHRQ Task Order Officer (TOO) and the EPC work to balance, manage, or mitigate any potential conflicts of interest identified.

Technical Experts constitute a multi-disciplinary group of clinical, content, and methodological experts who provide input in defining populations, interventions, comparisons, or outcomes and identify particular studies or databases to search. The Technical Expert Panel is selected to provide broad expertise and perspectives specific to the topic under development. Divergent and conflicting opinions are common and perceived as healthy scientific discourse that fosters a thoughtful, relevant systematic review. Therefore, study questions, design, and methodological approaches do not necessarily represent the views of individual technical and content experts. Technical Experts provide information to the EPC to identify literature search strategies and suggest approaches to specific issues as requested by the EPC. Technical Experts do not do analysis of any kind; neither do they contribute to the writing of the report. They do not review the report, except as given the opportunity to do so through the peer or public review mechanism.

Members of the TEP must disclose any financial conflicts of interest greater than $5,000 and any other relevant business or professional conflicts of interest. Because of their unique clinical or content expertise, individuals are invited to serve as Technical Experts and those who present with potential conflicts may be retained. The AHRQ TOO and the EPC work to balance, manage, or mitigate any potential conflicts of interest identified.

Peer reviewers are invited to provide written comments on the draft report based on their clinical, content, or methodological expertise. The EPC considers all peer review comments on the draft report in preparing the final report. Peer reviewers do not participate in writing or editing of the final report or other products. The final report does not necessarily represent the views of individual reviewers.

The EPC will complete a disposition of all peer review comments. The disposition of comments for systematic reviews and technical briefs will be published 3 months after publication of the evidence report.

Potential peer reviewers must disclose any financial conflicts of interest greater than $5,000 and any other relevant business or professional conflicts of interest. Invited peer reviewers with any financial conflict of interest greater than $5,000 will be disqualified from peer review. Peer reviewers who disclose potential business or professional conflicts of interest can submit comments on draft reports through the public comment mechanism.

EPC core team members must disclose any financial conflicts of interest greater than $1,000 and any other relevant business or professional conflicts of interest. Direct financial conflicts of interest that cumulatively total more than $1,000 will may result in disqualification as an EPC core team investigator or a mitigation plan. No EPC team member has conflicts to disclose.

This project is funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) and executed under AHRQ, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services through Contract No. 75Q80120D00006. The TOO will review contract deliverables for adherence to contract requirements and quality. The authors of this report will be responsible for its content. Statements in the report should not be construed as endorsement by PCORI, AHRQ, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

This protocol will be registered in the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO).