Publication Date: March 1, 2023

Amendment Date(s): April 10, 2023, May 3, 2023, July 10, 2023

The term genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM) describes the spectrum of vulvovaginal and urinary symptoms, as well as physical changes, resulting from declining estrogen and androgen concentrations in the female genitourinary tract.1 Vulvovaginal symptoms include dryness, burning, and irritation; dyspareunia; and bleeding during intercourse. Urinary symptoms include urgency, dysuria, and recurrent urinary infections. Physical changes and signs are varied and include labial atrophy, vaginal dryness, introital stenosis, and clitoral atrophy. The vaginal surface may be friable and hypopigmented, with petechiae, ulcerations, and tears; urethral findings may include caruncles, prolapse, or polyps.2

Since the introduction of the term GSM in 2014,1 there has been no consensus about the number or type (vulvovaginal, urinary, or sexual) of symptoms needed to diagnose GSM, nor a requirement for identifying physical signs. In practice, a clinical diagnosis of GSM is usually made based on the presence of symptoms in a post-menopausal woman, with or without physical findings, after ruling out other etiologies or co-occurring pathologies, such as infectious vaginitis, vulvar lichen sclerosis, dermatitis, or lichen planus. Objective measures of vaginal atrophy, such as an elevated vaginal pH or left-shifted Vaginal Maturation Index (VMI), are often reported in research studies, but have not been required for clinical diagnosis of GSM.3

GSM prevalence in post-menopausal women varies widely (estimates ranged from 13% to 87% in one recent review4), in part due to variation in the symptoms and signs evaluated, assessment tools used, and the demographics and settings of the study populations.4 Unlike vasomotor symptoms of menopause, prevalence and intensity of some genitourinary symptoms increase with advancing age.5, 6 GSM may be associated with reduced quality of life, sexual functioning, and may interfere with interpersonal relationships.7-12 Despite the potentially disruptive nature of GSM, only a minority of women report discussing GSM symptoms with their clinicians.13, 14

Given the low level of spontaneous symptom reporting, several organizations recommend GSM screening.15-17 However, few tools have been validated for GSM assessment and existing tools are limited to vulvovaginal symptoms.18, 19 The urinary symptoms associated with GSM are also associated with other common urinary conditions in older women, such as reduced bladder capacity, idiopathic overactive bladder, and detrusor overactivity, making identification, evaluation, and treatment of these symptoms complex.2 A causal relationship between reduced hormone levels and urinary symptoms remains controversial. Some have questioned whether GSM meets the definition of a disease syndrome. As a result, the optimal approach to screening, identification, and evaluation of GSM remains uncertain.

The range of GSM treatments has increased substantially in recent years. In addition to traditional therapies (vaginal or systemic estrogen, vaginal lubricants and moisturizers), new hormonal approaches (oral ospemifene, vaginal dehydroepiandrosterone [DHEA]), complementary therapies, oral and vaginal supplements, and energy-based treatment (EBT) with laser and radiofrequency devices have emerged. Randomized trials are short term, with little long-term efficacy, adherence, or harms data. Consequently, guidance for longer-term follow-up, surveillance, and management of special populations, such as women with a history of breast cancer, has relied on expert consensus in the absence of robust evidence.16, 17, 20

Purpose of the Review

This systematic review will examine the Key Questions (KQs) as outlined below. The American Urological Association nominated this topic to the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), which contracted with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to conduct the review. Given the range of symptoms associated with GSM, the lack of definitive diagnostic criteria, the impact of these symptoms, and the increasing number and range of available treatments, this SR will assist clinicians, patients, and other stakeholders to make informed decisions about screening, evaluation, and treatment.

Introduction: After discussion with key informants and our team’s content and methods experts, we chose to interpret the term “screening” in KQ1 as identifying underreported, symptom-based conditions (similar to screening for anxiety and depression), rather than “screening” for an asymptomatic condition. Based on input from public commenters, key informants, and members of a Technical Expert Panel, we have drafted the following key questions:

- Key Question 1: What is the effectiveness and harms of screening strategies to identify GSM in postmenopausal women? Does screening impact patient reported symptoms or improve quality of life?

- Key Question 2: What is the effectiveness and comparative effectiveness of hormonal, non-hormonal, and energy-based interventions when used alone or in combination for treatment of GSM symptoms? Which treatments show improvement for which symptoms?

- Key Question 3: What are the harms (and comparative harms) of hormonal, non-hormonal, and energy-based interventions for GSM symptoms?

- Key Question 4: What is the appropriate follow-up interval to assess improvement, sustained improvement, or regression of symptoms of GSM in women treated with hormonal, non-hormonal, and energy-based interventions?

- Key Question 5: What is the effectiveness, comparative effectiveness, and harms of endometrial surveillance among women who have a uterus and are using hormonal therapy for GSM?

For all key questions, how do the findings vary for women with a history of breast cancer or other hormone-related cancers, a high risk of cancer, or conditions such as primary ovarian insufficiency, women experiencing surgical menopause, gender diverse individuals, and within subgroups defined by severity of GSM symptoms, and patient characteristics (i.e., by age, race, socioeconomic status, etc.).

- Please see Table 1 for PICOTS.

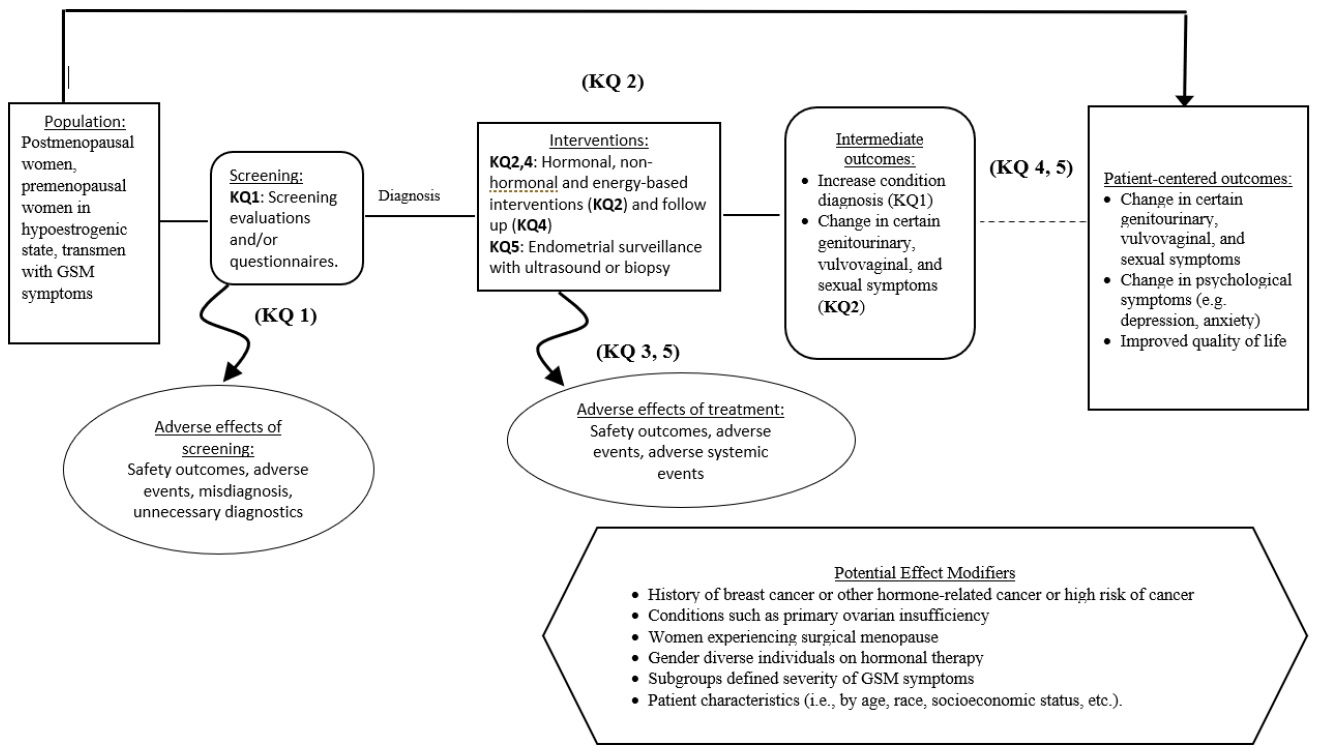

Figure 1. Analytical Framework for Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause

Figure 1: This figure depicts the key questions within the context of the PICOTS described above. In general, the figure illustrates how screening or case-finding may identify patients with GSM, who may then be treated with hormonal, non-hormonal, or energy-based interventions. These interventions may result in intermediate outcomes such as change in genitourinary, vulvovaginal, or sexual symptoms and/or patient-centered outcomes such as change in psychological symptoms or quality of life. Also, adverse events may occur at any point after patients are screened.

A. Criteria for Inclusion/Exclusion of Studies in the Review

Studies will be included in the review based on the PICOTS framework outlined above and the study-specific inclusion criteria described in Table 1.

Table 1. Draft Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, Timing, Setting/Study Design (PICOTS)

| Inclusion | Exclusion | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | ||

| KQ1: | Postmenopausal women | |

| KQ2-4: | Postmenopausal women, premenopausal women in hypoestrogenic state, or gender diverse individuals on hormonal therapy, with one or more symptom of GSM | Individuals with genitourinary symptoms for reasons other than GSM |

| KQ5: | Patients with a uterus using hormonal therapy primarily for GSM symptoms | Patients using hormonal therapy for reasons other than GSM |

| Interventions | ||

| KQ1: | Screening evaluations and/or questionnaires | Physical exam |

| KQ2-4: | Hormonal Interventions: Systemic estrogen for GSM, vaginal estrogen therapy, including vaginal cream, tablets, inserts or ring, selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM), intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), vaginal testosterone, compounded and bioidentical hormonal therapies; phytoestrogens

Energy-based interventions: CO2 laser, Erbium: YAG, radio-frequency laser Non-hormonal interventions: Over-the-counter non-hormone vaginal lubricants and moisturizers, hyaluronic acid, herbal therapies/supplemental alternatives, vitamin D, vitamin E, probiotics, oxytocin vaginal gel, pelvic floor physical therapy to treat vaginal or sexual symptoms of GSM. For KQ4. Assess different durations of follow-up |

Menopausal hormone therapy only for reasons other than GSM,

Laser therapy for anatomic areas other than the vagina, Pelvic floor physical therapy for urinary incontinence |

| KQ5: | Endometrial surveillance with ultrasound or biopsy | |

| Comparison | ||

| KQ1: | Usual care | |

| KQ2-4: | Effectiveness: Placebo, inactive control, sham

Comparative Effectiveness: Another hormonal, non-hormonal, or energy-based intervention For KQ4. Assess different durations of follow up |

|

| KQ5: | Usual care, or different type or level of surveillance | |

| Outcomes | ||

| KQ1: | Diagnosis of GSM, potential harms: misdiagnosis as another condition with similar presentation such as inflammatory dermatologic conditions, malignancy, infections, or presence of symptoms prior to menopause. Progressing to unnecessary diagnostics for the index patient such as vaginal or endometrial biopsy. | |

| KQ 1, 2&4: | Change in symptoms:

Genitourinary symptoms: urinary frequency, urinary urgency, nocturia, dysuria, recurrent urinary tract infections Other urinary symptoms (outcomes evaluated for interventions other than PFMT): urinary urge incontinence, overactive bladder Genital signs and symptoms: urethral caruncle, urethral prolapse, vaginal atrophy or atrophic vaginitis, vaginal dryness, vaginal / vulvar irritation, vaginal soreness, vaginal lubrication, vaginal pain Sexual symptoms: dyspareunia, orgasmic dysfunction, low libido, decreased arousal, sexual desire, sexual function, bleeding associated with sexual activity Psychological symptoms: depression, anxiety, quality of life, partner satisfaction |

Serum hormone concentration,

Stress incontinence |

| KQ3&5: | Safety outcomes: breast cancer, breast cancer recurrence or progression, breast tenderness, cardiovascular risk, endometrial cancer (KQ5), post-menopausal bleeding (KQ5), endometrial hyperplasia (KQ5), endometrial thickness (KQ5)

Adverse events: worsening or onset of urinary, genital, or sexual symptoms: vaginal burning, vaginal bleeding, vaginal discharge, vaginal scarring, vaginal stenosis; pelvic pain; dyspareunia; urethral strictures; meatal stricture/stenosis. Systemic adverse events: chronic pain, stroke; VTE (DVT or PE); death; hot flashes; headache; breast pain; cramps; bloating; nausea; vomiting |

|

| Timing | ||

| All KQ | Intervention: any Outcomes: any | |

| Setting | ||

| All KQ | Any | |

| Study design | ||

| KQ1 | RCTs and prospective observational studies with concurrent comparison group and analytic techniques to control for sample selection bias; systematic reviews of these study designs that assessed ROB of included studies using validated tools. | |

| KQ2 | RCTs or systematic review of RCTs that assessed ROB of included studies using validated tools. | |

| KQ3 | RCTs and prospective observational studies with concurrent comparison group and analytic techniques to control for sample selection bias; systematic reviews of these study designs that assessed ROB of included studies using validated tools. | |

| KQ4 | RCTs or systematic review of RCTs that assessed ROB of included studies using validated tools. | |

| KQ5 | RCTs and prospective observational studies with concurrent comparison group and analytic techniques to control for sample selection bias; systematic reviews of these study designs that assessed ROB of included studies using validated tools. | |

| Language | English only (due to resource limitations) | |

| Geographic Location | Any | |

| Study size | N=20 or more participants analyzed per study arm for RCTs | |

| Publication date | Any | |

Abbreviations: CO2=carbon dioxide; DHEA=dehydroepiandrosterone; DVT=deep venous thromboembolism; GSM=Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause; KQ=key question; PE=pulmonary embolism; PFMT=pelvic floor muscle training; RCT=randomized controlled trial; SERM=selective estrogen receptor modulator; VTE= venous thromboembolism

B. Searching for the Evidence: Literature Search Strategies for Identification of Relevant Studies to Answer the Key Questions

We will develop multiple search strategies for different relevant databases (Medline®, Embase®, and the Cochrane Central trials database) incorporating vocabulary and natural language relevant to the KQs (Appendix A).

Search results will be downloaded to EndNote X9 and screened in DistillerSR (Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Canada). Two independent investigators will review titles and abstracts using predefined criteria. Two independent investigators will perform full-text screening to determine if inclusion criteria are met. Differences in screening decisions will be resolved by consultation between investigators, and, if necessary, consultation with a third investigator. Throughout the screening process, team members will meet regularly to discuss training material and issues as they arise to ensure consistency of inclusion criteria application. Multiple publications relating to the same study will be mapped to unique study.

We will supplement our bibliographic database searches with citation searching of relevant systematic reviews and original research. Additionally, we will search for grey literature on ClinicalTrials.gov to identify completed and ongoing studies. Information from grey literature will also be used to assess publication and reporting bias and inform future research needs. Additional grey literature will be solicited through a notice in the Federal Register and Scientific Information Packets and other information solicited through the AHRQ Effective Health Care website.

Systematic reviews that directly address a question in our review and assess ROB for included individual studies using appropriate validated tools will be assessed for quality. We will use A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) 2 criteria for systematic reviews of treatment studies,21 and modified AMSTAR 2 criteria for systematic reviews of diagnostic test studies.

C. Data Abstraction and Data Management

Data fields to be extracted will include author, year of publication, sponsorship, setting, subject inclusion and exclusion criteria, intervention and control characteristics, sample size, follow-up duration, participant baseline age, race, and results of primary outcomes and adverse effects. Relevant data will be extracted into extraction forms created in Microsoft Excel or Distiller SR. Data will be extracted to evidence and outcomes tables by one investigator and reviewed and verified for accuracy by a second investigator. We will not extract data from high risk of bias studies or for outcomes that are high risk of bias.

Systematic reviews determined to be high quality will be used to replace de novo data extraction processes for specific population, treatment, or outcome comparisons deemed sufficiently relevant. Individual studies from included systematic reviews will be tracked for contribution to unique population, treatment, or outcome comparisons to avoid double-counting study results.

D. Assessment of Methodological Risk of Bias of Individual Studies

Risk of bias of eligible studies by outcome will be assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool 2.0 for RCTs and the ROBINS-I for observational studies.22,23 Components include participant group assignment (random sequence generation, allocation concealment), blinding (performance and detection bias), completeness of follow-up (attrition bias), analyses and outcome reporting consistent with predefined protocols (selective reporting bias) and other issues (such as appropriateness of analytic approach).

One investigator will independently assess risk of bias for eligible studies by outcome; a second investigator will review each risk of bias assessment. Investigators will consult to reconcile any discrepancies in risk of bias assessments. Overall risk of bias assessments for each study-outcome will be classified as low, high, or unclear based upon the collective risk of bias across components and confidence that the study results for a given outcomes are believable given the study’s limitations.

E. Data Synthesis

Results will be organized first by key question. For key questions 2-4, results will be organized by treatment comparison, and then by targeted treatment outcome and harms. For studies with low and moderate risk of bias, we first will describe the results in evidence tables. When a comparison is adequately addressed by a previous high quality systematic review and no new studies are available, we will reiterate the conclusions drawn from that review. When new eligible trials were published since the search date of the prior review, previous systematic review data will be synthesized with data from these new trials. We will synthesize evidence for each unique comparison with meta-analysis when possible and appropriate. We will assess the clinical and methodological heterogeneity and variation in effect size to determine appropriateness of pooling data.24 We will synthesize data using a Hartung, Knapp, Sidik, and Jonkman (HKSJ)25 random effects model in R (A language and environment for statistical computing, https://www.R-project.org/). We will calculate risk ratios (RR) and absolute risk differences (RD) with the corresponding 95 percent confidence intervals (CI) for binary outcomes and weighted mean differences (WMD) and/or standardized mean differences (SMD) with the corresponding 95 percent CIs for continuous outcomes if combining similar outcomes measured with different instruments.

We will identify heterogeneity (inconsistency) through visual inspection of the forest plots to assess the amount of overlap of CIs, 95% prediction intervals, Ƭ2, and the I2 statistic to assess the impact of heterogeneity on the meta-analysis.26 We will interpret the I2 statistic as follows27

- 0% to 40%: may not be important

- 30% to 60%: may indicate moderate heterogeneity

- 50% to 90%: may indicate substantial heterogeneity

- 75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity

When we find heterogeneity, we will attempt to determine possible reasons for it by examining individual study and subgroup characteristics.

F. Grading the Evidence Quality for Major Comparisons and Outcomes

The American Urological Association (AUA) intends to use this evidence report to update their guidelines. Because this organization uses Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE)28 for rating evidence certainty, we will use the GRADE approach to assess the overall quality of evidence.

We will present the overall quality or certainty of the evidence for each outcome according to the GRADE approach. We will GRADE the 8 consensus outcomes identified in the Core Outcomes in Menopause (COMMA) review.29 The GRADE approach assesses five criteria which measure either internal validity (risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, publication bias) or external validity (directness of results)28. RCTs start out as high quality and may be rated down for any one of the five criteria. Non-randomized trials start out as low-quality evidence, and are assessed on additional criteria (evidence of a large magnitude of effect, a dose-effect relationship, and for the effect of residual opposing confounding). For each comparison, one of the evidence reviewers will rate the quality of evidence for each outcome as high, moderate, low, or very low using GRADEpro GDT (www.gradepro.org). These ratings will then be reviewed by a second evidence reviewer. We will resolve any discrepancies by consensus, or by discussion with a third evidence reviewer if needed.

For each comparison, we will present a summary of the evidence for the main outcomes in a 'Summary of findings' table as well as a full Evidence Profile, which provides key information about the best estimate of the magnitude of the effect in relative terms and absolute differences for each relevant comparison of alternative management strategies; numbers of participants and studies addressing each important outcome; and the rating of the overall confidence in effect estimates for each outcome.30 If meta-analysis is not possible, we will present results in a narrative 'Summary of findings' table or Evidence Profile.

- Portman DJ GM, Panel VATCC. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: new terminology for vulvovaginal atrophy from the International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health and the North American Menopause Society. Climacteric. 2014;17(5):557-63. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12686. PMID: 25155380

- Mitchell CM WL. Genitourinary changes with aging. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics. 2018;45(4):737-50. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2018.07.010. PMID: 30401554

- Weber M, Limpens J, Roovers J. Assessment of vaginal atrophy: a review. Int Urogynecol J 2015;26:15-28. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-014-2464-0. PMID: 30401554

- Mili N PS, Armeni A, Georgopoulos N, Goulis DG, Lambrinoudaki I. Genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a systematic review on prevalence and treatment. Menopause. 2021;28(6):706-16. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001752. PMID: 33739315

- Kingsberg SA WS, Magnus L, Krychman ML. Vulvar and vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women: findings from the REVIVE (REal Women's VIews of Treatment Options for Menopausal Vaginal ChangEs) survey. The journal of sexual medicine. 2013;10(7):1790-9. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12190. PMID: 23679050

- Cagnacci A XA, Sclauzero M, Venier M, Palma F, Gambacciani M, writing group of the ANGEL study. Vaginal atrophy across the menopausal age: results from the ANGEL study. Climacteric. 2019;22(1):85-9. doi: 10.1080/13697137.2018.1529748. PMID: 30601037

- Nappi R PS. Impact of vulvovaginal atrophy on sexual health and quality of life at postmenopause. Climacteric. 2014;17(1):3-9. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2013.871696. PMID: 24423885

- Nappi RE KS, Maamari R, Simon J. The CLOSER (CLarifying Vaginal Atrophy's Impact On SEx and Relationships) survey: implications of vaginal discomfort in postmenopausal women and in male partners. The journal of sexual medicine. 2013;10(9):2232-41. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12235. PMID: 23809691

- Nappi RE K-KM. Women's voices in the menopause: results from an international survey on vaginal atrophy. Maturitas. 2010;67(3):233-8. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.08.001. PMID: 20828948

- Pinkerton JV BA, Komm BS, Abraham L. Relationship between changes in vulvar-vaginal atrophy and changes in sexual functioning. Maturitas. 2017;100:57-63. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.03.315. PMID: 28539177

- Moral E DJ, Carmona F, Caballero B, Guillán C, González P, Suárez-Almarza J, Velasco-Ortega S, Nieto Magro C. The impact of genitourinary syndrome of menopause on well-being, functioning, and quality of life in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2018. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001148. PMID: 29944636

- Parish SJ NR, Krychman ML, Kellogg-Spadt S, Simon JA, Goldstein JA, Kingsberg SA. Impact of vulvovaginal health on postmenopausal women: a review of surveys on symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy. International Journal of Women's Health. 2013;5:437-47. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S44579. PMID: 23935388

- Kingsberg SA KM, Graham S, Bernick B, Mirkin S. The women's EMPOWER survey: identifying women's perceptions on vulvar and vaginal atrophy and its treatment. The journal of sexual medicine. 2017;14(3):413-24. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.01.010. PMID: 28202320

- Simon JA K-KM, Goldstein J, Nappi RE. Vaginal health in the United States: results from the Vaginal Health Insights, Views & Attitudes survey. Menopause.20(10):1043-8. doi: 10.1097/GME.0b013e318287342d. PMID: 23571518

- Stuenkel CA DS, Gompel A, Lumsden MA, Hassan Murad M, Pinkerton JV, Santen RJ. Treatment of symptoms of the menopause: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2015;100(11):3975-4011. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-2236. PMID: 26444994

- Faubion SS KS, Shifren JL, Mitchell C, Kaunitz AM, Larkin LC, Kellogg Spadt S, Clark A, Simon JA. The 2020 genitourinary syndrome of menopause position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2020;27(9):976-92. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001609. PMID: 32852449

- Faubion SS LL, Stuenkel CA, Bachmann GA, Chism LA, Kagan R, Kaunitz AM, Krychman ML, Parish SJ, Partridge AH, Pinkerton JV, Rowen TS, Shapiro M, Simon JA, Goldfarb SB, Kingsberg SA. Management of genitourinary syndrome of menopause in women with or at high risk for breast cancer: consensus recommendations from The North American Menopause Society and The International Society for the Study of Women's Sexual Health. Menopause. 2018;25(6):596-608. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001121. PMID: 29762200

- Gabes M KH, Stute P, Apfelbacher CJ. Measurement properties of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) for women with genitourinary syndrome of menopause: a systematic review. Menopause. 2019;26(11):1342-53. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001390. PMID: 31688581

- Huang AJ GS, Kuppermann M, Nakagawa S, Van Den Eeden SK, Brown JS, Richter HE, Walter LC, Thom, D, Stewart AL. The day-to-day impact of vaginal aging questionnaire: A multidimensional measure of the impact of vaginal symptoms on functioning and well-being in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2015;22(2):144-54. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000000281. PMID: 24983271

- R F. The Use of Vaginal Estrogen in Women With a History of Estrogen-Dependent Breast Cancer. Obstet Gynecol [Internet]. 2016 26901334]; 127(3):93-6. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001351. PMID: 26901334

- Shea BJ RB, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, Moher D, Tugwell P, Welch V, Kristjansson E, Henry DA. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017:358. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008. PMID: 28935701

- Sterne JAC SJ, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng HY, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, Emberson JR, Hernán MA, Hopewell S, Hróbjartsson A, Junqueira DR, Jüni P, Kirkham JJ, Lasserson T, Li T, McAleenan A, Reeves BC, Shepperd S, Shrier I, Stewart LA, Tilling K, White IR, Whiting PF, Higgins JPT. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:i4898. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4898. PMID: 31462531

- Sterne JA HM, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, Henry D, Altman DG, Ansari MT, Boutron I, Carpenter JR, Chan AW, Churchill R, Deeks JJ, Hróbjartsson A, Kirkham J, Jüni P, Loke YK, Pigott TD, Ramsay CR, Regidor D, Rothstein HR, Sandhu L, Santaguida PL, Schünemann HJ, Shea B, Shrier I, Tugwell P, Turner L, Valentine JC, Waddington H, Waters E, Wells GA, Whiting PF, Higgins JP. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. PMID: 27733354

- Fu R GG, Grant M, Shamliyan T, Sedrakyan A, Wilt TJ, Griffith L, Oremus M, Raina P, Ismaila A, Santaguida P, Lau J, Trikalinos TA. Conducting quantitative synthesis when comparing medical interventions: AHRQ and the Effective Health Care Program. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2011;64(11):1187-97. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.08.010. PMID: 21477993

- IntHout J IJ, Borm GF. The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC medical research methodology. 2014;14(1):25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-25. PMID: 24548571

- Higgins JP TS, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557-60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. PMID: 12958120

- Deeks J HJ, Altman D. Chapter 9.5.2: Identifying and measuring heterogeneity. In: Higgins JPT GS, editor. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: Version 510. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011.

- Guyatt GH OA, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Schünemann HJ; GRADE Working Group. What is "quality of evidence" and why is it important to clinicians? . BMJ. 2008;336(7651):995-8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39490.551019.BE. PMID: 18456631

- Lensen S BR, Carpenter JS, Christmas M, Davis SR, Giblin K, Goldstein SR, Hillard T, Hunter MS, Iliodromiti S, Jaisamrarn U, Khandelwal S, Kiesel L, Kim BV, Lumsden MA, Maki PM, Mitchell CM, Nappi RE, Niederberger C, Panay N, Roberts H, Shifren J, Simon JA, Stute P, Vincent A, Wolfman W, Hickey M. A core outcome set for genitourinary symptoms associated with menopause: the COMMA (Core Outcomes in Menopause) global initiative. Menopause. 2021;28(8):859-66. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001788. PMID: 33973541

- Guyatt G OA, Sultan S, Brozek J, Glasziou P, Alonso-Coello P, Atkins D, Kunz R, Montori V, Jaeschke R, Rind D, Dahm P, Akl EA, Meerpohl J, Vist G, Berliner E, Norris S, Falck-Ytter Y, Schünemann HJ. GRADE guidelines: 11. Making an overall rating of confidence in effect estimates for a single outcome and for all outcomes. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2013;66(2):151-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.01.006. PMID: 22542023

| Abbreviation | Definition |

|---|---|

|

AHRQ |

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality |

|

AMSTAR |

A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews |

|

AUA |

American Urological Association |

|

CAUTI |

Catheter-associated urinary tract infection |

|

CI |

Confidence interval |

|

CO2 |

Carbon dioxide |

|

COMMA |

Core Outcomes in Menopause |

|

CVA |

Cerebrovascular accident |

|

DHEA |

Dehydroepiandrosterone |

|

DVT |

Deep venous thromboembolism |

|

EBT |

Energy-based treatment |

|

EPC |

Evidence-based Practice Center |

|

GRADE |

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation |

|

GSM |

Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause |

|

HKSJ |

Hartung, Knapp, Sidik, and Jonkman |

|

ISSWSH |

International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health |

|

KQ |

Key Question |

|

PE |

Pulmonary embolism |

|

PFMT |

Pelvic floor muscle training |

|

PICOTS |

Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes, Timing, and Study design/setting |

|

RCT |

Randomized controlled trial |

|

RD |

Risk difference |

|

ROB |

Risk of bias |

|

ROBINS-I |

Risk Of Bias In Non-Randomized Studies - of Interventions |

|

RR |

Risk ratio |

|

SERM |

Selective estrogen receptor modulator |

|

SMD |

Standardized mean differences |

|

SR |

Systematic Review |

|

TOO |

Task Order Officer |

|

US |

United States |

|

VMI |

Vaginal Maturation Indices |

|

VTE |

Venous thromboembolism |

|

WMD |

Weighted mean differences |

Amendment Date(s): April 10, 2023, May 3, 2023, July 10, 2023

|

Date |

Section |

Original Protocol |

Revised Protocol |

Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

4-10-2023 |

Methods (Table 1. PICOTS) |

All included studies were intended for risk of bias (ROB) assessment. |

All studies of non-hormonal interventions (except for moisturizers) will be reported in an evidence map. These studies will not be assessed for risk of bias, but trial characteristics will be described in the results at the level of information appropriate for an evidence map. |

This criterion was developed to address the large number of potentially eligible studies including many "one-off" (i.e., 1 or 2 studies) non-hormonal interventions. This change conserves review resources for synthesizing studies for intervention/outcome combinations most likely to contribute a finding that can inform guidelines, rather than reporting a list of heterogeneous trials. |

| 4-10-2023 | Methods (Table 1. PICOTS) | Included systemic estrogen as an intervention of interest. | Exclude systemic estrogen (oral/transdermal or high dose vaginal) as an intervention of interest, though include as a comparator or co-treatment. Eg, exclude systemic estrogen vs. placebo, exclude studies comparing doses/routes/formulations of systemic estrogen. If systemic estrogen was combined with an eligible intervention: exclude if it is not possible to isolate the effect of the eligible intervention. | Systemic estrogen has primarily been used for vasomotor symptoms and has been tested for other menopausal symptoms, but is typically not recommended for GSM alone, due to potential systemic side effects. In an effort to focus our review of estrogen studies on those most relevant to the treatment of GSM, we prioritized local/vaginal estrogen studies and limited systemic estrogen studies to those comparing GSM-specific treatments to systemic estrogen, or those testing the addition of GSM-specific treatments to systemic estrogen. |

| 4-10-2023 | Methods (Table 1. PICOTS) | N/A | Exclude interventions not available in the US (eg, estriol) and obsolete interventions no longer available in the US (eg, 25 mcg estradiol tablets). | This language was not explicitly used in our initial PICOTS but has since been added to reflect previous discussions with our partners/TOO. We agreed there was no benefit of including studies of interventions not available in the U.S. Since one of the goals of this review is to inform future AUA management guidelines, we focused on U.S.-available treatments. |

| 5-3-2023 | Methods (Table 1. PICOTS) | Allowed inclusion of systematic reviews (SRs) of any eligible primary study design for each KQ with the intent to use high-quality SRs to supplement or substitute for primary studies. | Exclude SRs. | As intended, SRs were initially included and reviewed to determine if any could be used to supplement or substitute for primary studies. After reviewing the initially included SRs, we found that none covered sufficient studies/categories to reasonably replace individual studies. Therefore, SRs were excluded, and we used the SR reference lists to identify any missed primary studies. |

| 5-3-2023 | Methods (Table 1. PICOTS) | Allowed for any timing of outcome assessment. | We applied an 8-week minimum requirement for follow-up within RCTs and prospective observational studies and a 1-year minimum requirement for "other" study designs (i.e., studies of laser interventions investigating long-term harms). Both of these follow-up requirements were from treatment initiation (i.e., at least 8 weeks/1 year since treatment initiation). | GSM is a long-term chronic condition that typically begins post-menopause and requires ongoing treatment. Therefore, we focused on studies with a minimum of 8 weeks follow-up from treatment initiation. Given the high volume of initially eligible studies, this requirement allowed us to focus on studies that assess more clinically relevant outcomes, rather than short-term outcomes. |

| 7-10-2023 |

Methods (Table 1. PICOTS) |

Phytoestrogens were classified as "hormonal" interventions for KQ2-4. Oxytocin was classified as a "non-hormonal" intervention for KQ2-4 |

Phytoestrogens are classified as “non-hormonal” interventions for KQ2-4. Oxytocin is classified as a "hormonal" intervention for KQ2-4. |

Phytoestrogens include multiple compounds derived from diverse plant sources that have varying strengths and effects on estrogen receptors. We reclassified them as non-hormonal interventions to be consistent with existing literature, including prior systematic reviews and guidelines. Oxytocin is a hypothalamic hormone so we reclassified it with the other non-estrogen hormones. |

The EPC refined and drafted the key questions after review of the public comments, and input from Key Informants. This input is intended to ensure that the key questions are specific and relevant.

Key Informants are the end-users of research; they can include patients and caregivers, practicing clinicians, relevant professional and consumer organizations, purchasers of health care, and others with experience in making health care decisions. Within the EPC program, the Key Informant role is to provide input into the decisional dilemmas and help keep the focus on Key Questions that will inform health care decisions. The EPC solicits input from Key Informants when developing questions for the systematic review or when identifying high-priority research gaps and needed new research. Key Informants are not involved in analyzing the evidence or writing the report. They do not review the report, except as given the opportunity to do so through the peer or public review mechanism.

Key Informants must disclose any financial conflicts of interest greater than $5,000 and any other relevant business or professional conflicts of interest. Because of their role as end-users, individuals are invited to serve as Key Informants and those who present with potential conflicts may be retained. The AHRQ Task Order Officer (TOO) and the EPC work to balance, manage, or mitigate any potential conflicts of interest identified.

Technical Experts constitute a multi-disciplinary group of clinical, content, and methodological experts who provide input in defining populations, interventions, comparisons, or outcomes and identify particular studies or databases to search. They are selected to provide broad expertise and perspectives specific to the topic under development. Divergent and conflicting opinions are common and perceived as health scientific discourse that results in a thoughtful, relevant systematic review. Therefore, study questions, design, and methodological approaches do not necessarily represent the views of individual technical and content experts. Technical Experts provide information to the EPC to identify literature search strategies and recommend approaches to specific issues as requested by the EPC. Technical Experts do not do analysis of any kind nor do they contribute to the writing of the report. They have not reviewed the report, except as given the opportunity to do so through the peer or public review mechanism.

Technical Experts must disclose any financial conflicts of interest greater than $10,000 and any other relevant business or professional conflicts of interest. Because of their unique clinical or content expertise, individuals are invited to serve as Technical Experts and those who present with potential conflicts may be retained. The TOO and the EPC work to balance, manage, or mitigate any potential conflicts of interest identified.

Peer reviewers are invited to provide written comments on the draft report based on their clinical, content, or methodological expertise. The EPC considers all peer review comments on the draft report in preparation of the final report. Peer reviewers do not participate in writing or editing of the final report or other products. The final report does not necessarily represent the views of individual reviewers. The EPC will complete a disposition of all peer review comments. The disposition of comments for systematic reviews and technical briefs will be published three months after the publication of the evidence report.

Potential Peer Reviewers must disclose any financial conflicts of interest greater than $10,000 and any other relevant business or professional conflicts of interest. Invited Peer Reviewers may not have any financial conflict of interest greater than $10,000. Peer reviewers who disclose potential business or professional conflicts of interest may submit comments on draft reports through the public comment mechanism.

EPC core team members must disclose any financial conflicts of interest greater than $1,000 and any other relevant business or professional conflicts of interest. Related financial conflicts of interest that cumulatively total greater than $1,000 will usually disqualify EPC core team investigators.

This project was funded under Contract No. 75Q80120D00008 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Task Order Officer reviewed contract deliverables for adherence to contract requirements and quality. The authors of this report are responsible for its content. Statements in the report should not be construed as endorsement by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Ovid MEDLINE(R) ALL <1946 to January 30, 2023>

1 climacteric/ or menopause/ or menopause, premature/ or postmenopause/ or primary ovarian insufficiency/ or (climacteric or estrogen-deficien* or hypoestrogeni* or menopaus* or postmenopaus* or post-menopaus* or primary ovarian insufficiency).ti,ab. 119541

2 ((genitourinary or genito-urinary) adj3 (symptom* or syndrome)).ti,ab. 1032

3 female urogenital diseases/ or vaginal diseases/ or vaginal discharge/ or vaginitis/ or atrophic vaginitis/ or vulvovaginitis/ or vulvitis/ or vulvodynia/ or (urogenital or vaginal atrophy or vaginal burning or vaginal discharge or vaginal dryness or vaginal itch* or vagina* pain* or vaginitis or vulvitis or vulvovaginitis or vulvovaginal atrophy).ti,ab. or (inflammation adj3 (vagin* or vulva*)).ti,ab. 35228

4 Dysuria/ or lower urinary tract symptoms/ or nocturia/ or urinary bladder, overactive/ or Urethral Diseases/ or Urethritis/ or urinary incontinence/ or urinary incontinence, urge/ or (dysuria or urinary symptom* or nocturia or overactive bladder or urethral caruncle or urethral prolapse or urethritis or incontinence or recurrent urinary tract infection*).ti,ab. 91267

5 dyspareunia/ or pelvic pain/ or sexual dysfunction, physiological/ or (dyspareunia or sexual dysfunction or pelvic pain).ti,ab. 34092

6 or/2-5 152259

7 1 and 6 6179

8 exp Estrogens/ or Androgens/ or Estrogen replacement therapy/ or Testosterone/ or Dehydroepiandrosterone/ or Progesterone/ or exp Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators/ or (estrogen* or oestrogen* or estradiol or oestradiol or bioidentical hormon* therap* or compound* hormon* therap* or androgens or ospemifene or phytoestrogens or prasterone or progesterone or selective estrogen receptor modulators or vaginal testosterone or intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone or vaginal dehydroepiandrosterone or intravaginal DHEA or vaginal DHEA).ti,ab. 419945

9 Lasers, Gas/tu or Laser Therapy/ or (carbon dioxide laser or CO2 laser or erbium aluminum laser or erbium laser or Er:YAG laser or laser therap* or radiofrequency).ti,ab. 91020

10 Acupuncture Point/ or Acupuncture Therapy/ or drugs, chinese herbal/ or Yoga/ or (acupuncture or herbal supplement* or pelvic floor physical therap* or pelvic floor therap* or pelvic floor training or yoga).ti,ab. 90913

11 Lubricants/ or hyaluronic acid/ or "vaginal creams, foams, and jellies"/ or Oxytocin/ or Probiotics/ or ((vagina* or intravagin*) adj2 (cream* or dilator* or foam* or gel* or hyaluronic acid or insert or jelly or jellies or lubricant* or moisturizer* or oxytocin or probiotic* or vitamin D or vitamin E)).ti,ab. 73598

12 ((nonhormon* or non-hormon*) adj2 (therap* or treatment*)).ti,ab. 592

13 or/8-12 669661

14 6 and 13 9892

15 7 or 14 12950

16 comment/ or editorial/ or letter/ or exp congress/ or clinical conference/ or consensus development conference/ or "Review"/ 5291922

17 (canine or canines or cow or cows or dog or dogs or mouse or mice or rabbit or rabbits or rat or rats).ti,ab. 3287242

18 Penile Erection/ or Erectile Dysfunction/ or Prostatic Neoplasms/ or (erectile dysfunction or penile or prostate or prostatic).ti. 222326

19 or/16-18 8612157

20 15 not 19 8002

21 limit 20 to english language 7028