Background and Objectives for the Systematic Review

Disruptive Behavior Disorders (DBDs) is a term used to describe a group of related psychiatric disorders of childhood and adolescence marked by temper tantrums, interpersonal aggression, and defiance. These disorders and related symptoms may manifest in young children as significant behavioral problems at home and difficulties at school. Children with the highest levels of disruptive behavior in early childhood, often experience persistent impairment1 and are at increased risk for negative developmental outcomes including substance abuse problems, school problems, and delinquent, violent, and antisocial or criminal behaviors in adolescence.2-14 As many of these problems persist into adulthood, the economic costs of DBDs are high.

DBDs are one of the most common child and adolescent psychiatric disorders, with 9 to 16 percent of youth diagnosed at some point during development,15-19 and estimates suggest that sub-clinical conduct problems may be as many as three times more common than those meeting formal clinical diagnostic criteria.2 DBDs are associated with increased risk for a wide range of negative developmental outcomes including substance abuse problems, school problems, and delinquent, violent, and antisocial or criminal behaviors.2-14 As many of these problems persist into adulthood, the economic costs of DBDs are high.

The etiology of DBDs is unknown but temperamental, biological and environmental factors are associated with increased risk. Temperamental risk factors include callous-unemotional traits, behavioral disinhibition, and indicators of limited executive functioning such as having a short attention span.20 Biological risk factors include lower salivary cortisol levels, lower baseline heart rate levels, and higher increases in heart rate in response to frustration.21,22 Low birthweight children also are at increased risk for DBDs.23,24 Environmental risk factors include prenatal exposure to maternal smoking, substance use, illness, and stress.23

Children who have experienced abuse and neglect, early separation from their parents including adoption, and maternal anxiety and depression are also at increased risk.23

Risk attributable to factors such as maternal smoking, substance use, and anxiety and depression during pregnancy have been addressed by more general public health campaigns. Although DBD-specific preventive interventions have been developed, practical considerations including training requirements and cost pose challenges to broad implementation.25,26

Treatment

General outpatient psychotherapy and psychotropic medication management are the most commonly used interventions, either alone or in combination.15,27-30 Psychosocial interventions have been developed for some patient subgroups and for some symptoms/symptom clusters. Examples of these interventions include youth-level interventions such as Aggression Replacement Training and Problem-Solving Skills Training; parent-level interventions including Helping the Non-compliant Child and Parent-Child Interaction Therapy; and family-level interventions such as Functional Family Therapy or Multi-Systemic Therapy.31-38 A recently published review indicated that psychosocial treatments had large effects on early behavior problems, but also reported considerable variability in the magnitude of effects among the 36 included studies.39

The use of psychotropic medications to manage disruptive behaviors has increased dramatically and has primarily, but not exclusively, been accounted for by increasing use of atypical antipsychotic medications.28-30,40 Using data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey and National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, Cooper and colleagues28 demonstrated that antipsychotic prescribing increased nearly five-fold from 8.6 per 1,000 U.S. children in 1995-96 to 39.4 per 1,000 U.S. children in 2001-02. Furthermore, the medication prescribing increases were greater for non-approved indications including DBDs than for approved indications such as schizophrenia, psychosis, Tourette’s syndrome, autism, and mental retardation.

There is wide range of medications used with a significant degree of decisional uncertainty around safety, efficacy, and which combinations to use.41 Classes of medications that have been studied for treatment of disruptive behaviors include antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, anticonvulsants, and psychostimulants.42 Combination therapy with antipsychotics and stimulants can be effective for patients with ADHD comorbid with DBD or aggression;43 however, superiority over monotherapy and tolerability of combined pharmacologic treatment is unclear.

Relevant systematic reviews and guidelines

We identified a number of systematic reviews and meta-analyses published in the last five years evaluating pharmacotherapy for youth with disruptive behaviors.43-51 Other recent reviews evaluated the effectiveness of parenting programs, cognitive behavior therapies, social skills, and other nonpharmacologic treatments such as acupuncture and dietary supplementation.52-61

The recently published Treatment of Maladaptive Aggression in Youth guidelines (T-MAY)62,63 from the Center for Education and Research on Mental Health Therapeutics (CERT) recommend psychosocial interventions and address the use of combination therapy. The T-MAY guidelines suggest initial medication management and psychosocial treatments to address any underlying condition, followed by use of an antipsychotic or mood stabilizer to treat persistent aggression.62,63 Data from high quality studies are needed to confirm these recommendations.

Anti-psychotic drugs have FDA approval for a limited set of specific indications in children, including bipolar and irritability associated with autism, although not for Disruptive Behavior Disorder. Nonetheless, pediatric use of both first and second-generation antipsychotics has rapidly increased in recent years, including in conditions for which they are not FDA indicated. Recent reviews have concluded that there is an absence of evidence from controlled studies on the long-term efficacy and safety of these drugs in children.64 Although there is a recent review of antipsychotics for pediatric patients, this review is not specific to disruptive behavior disorders and concludes that there are important gaps in the literature on the comparative effectiveness and relative safety of these drugs.65 The authors of a systematic review of antipsychotic and psychostimulant drug combination therapy for ADHD and DBD noted that most studies were performed over short time periods, several studies lacked blinding.43

A review from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) describes “promising” practices for treatment and prevention of disruptive behaviors in children.66

Despite the existence of these and other reviews of pharmacologic and psychosocial interventions, there remains an absence of clear and accessible guidance for best practice.

Decisional dilemmas

Wide variations in clinical management of DBDs, including the use of polypharmacy and tailored psychosocial approaches, frequently administered with little to no adherence to a standard protocol, are described in the literature. In the absence of clearly synthesized information about which interventions are most safe and effective for specific patient subgroups, it is difficult for healthcare providers to make informed treatment recommendations. For example, studies of Problem-Solving Skills Training and Parent-Child Interaction Therapy have reported positive results for children with DBDs, but it is unclear how healthcare providers should select between a child-level intervention, a parent-level intervention, and pharmacotherapy. The role of early risk factors, family ecology, and treatment history on treatment response remains unclear. Treatment decision dilemmas are further complicated for patients with medical and/or psychiatric comorbidities. The safety of atypical antipsychotics is an important concern.43,48-50

Challenges

Defining the population with disruptive behavior disorders is likely to be one of the most complex issues in this review. DBDs are a heterogeneous group of conditions; disruptive behaviors are also heterogeneous and are often present in the absence of a specific DBD diagnosis. Studies that are intended to assess treatment for conditions such as ADHD, for example, are likely to report changes in disruptive behaviors as outcomes. For this reason, and because a review of ADHD currently exists,67 we will focus the current review on studies in which the aim of treatment is a disruptive behavior, with or without a DBD diagnosis. This would exclude studies focusing on treating ADHD and other conditions that may include disruptive behaviors, (e.g., autism, developmental disability) but are not intended to assess treatments focused on reducing disruptive behaviors themselves.

It will be particularly important to understand diagnostic shifts both in assessing studies and in assessing applicability and putting the review into context. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth edition (DSM-IV) defines “Attention-Deficit and Disruptive Behavior Disorders” as a broad category of disorders usually first diagnosed in infancy, childhood or adolescence, and DBDs to include Oppositional Defiant Disorder, Conduct Disorder, and Disruptive Behavior Disorder, Not Otherwise Specified.68 DSM-V does not include a chapter for “disorders usually first diagnosed in infancy, childhood, or adolescence” but does include a chapter on “disruptive, impulse-control and conduct disorders.” This new chapter includes some (e.g., ODD, CD) but not all (e.g., ADHD) of the DBDs previously included in the “disorders usually first diagnosed in infancy, childhood, or adolescent” chapter, as well as other disorders (e.g., intermittent explosive disorder) which were previously included in other chapters of DSM-IV. In addition to the disruptive behaviors and DBDs noted above, other common disruptive behaviors include aggression leading to property damage or loss, violation of the rights of others, and criminality.68

The treatments for disruptive behaviors and disruptive behavior disorders include both psychological and pharmacologic approaches. Nonpharmacologic interventions are recommended as the initial strategy, but the clinical reality is that clinicians and families probably use both approaches at some point, possibly simultaneously, creating further decisional dilemmas related to co-therapy, polypharmacy, and the role of treatment history. We have, therefore, framed the Key Questions to ascertain the comparative effectiveness of various psychological and pharmacologic treatments aimed at disruptive behaviors, compared both within and between treatment types, and ascertain whether there are combinations of psychological and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches that are optimal. We anticipate that poor or incomplete intervention descriptions, specifically in the studies of psychosocial interventions, may narrow the options for synthesizing the results and limit the extent of applicability assessments.

The choice of outcomes on which to focus the analysis and particularly the strength of evidence is challenging for this review. There are many measures used to assess components of disruptive behavior, not all of which have been validated.

Finally, given the heterogeneity in study populations, it will be important to capture information on the participant characteristics including age, gender, and concomitant conditions and to consider whether these characteristics modify the effectiveness of the interventions.

Key Questions

The draft Key Questions (KQs), PICOTS, and Analytic Framework were posted for public comment (December 17, 2013 - January 10, 2014). The Key Questions were revised according to the comments received and are listed below. The PICOTS for the Key Questions are presented in Table 1.

Key Question 1

In children under 18 years of age treated for disruptive behaviors, are any psychosocial interventions more effective for improving short-term and long-term psychosocial outcomes than no treatment or other psychosocial interventions?

Key Question 2

In children under 18 years of age treated for disruptive behaviors, are alpha-agonists, anticonvulsants, beta-blockers, central nervous system stimulants, first-generation antipsychotics, second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors more effective for improving short-term and long-term psychosocial outcomes than placebo or other pharmacologic interventions?

Key Question 3

In children under 18 years of age treated for disruptive behaviors, what is the relative effectiveness of any psychosocial interventions compared with the pharmacologic interventions listed in Key Question 2 for improving short-term and long-term psychosocial outcomes?

Key Question 4

In children under 18 years of age treated for disruptive behaviors, are any combined psychosocial and pharmacologic interventions listed in Key Question 2 more effective for improving short-term and long-term psychosocial outcomes than individual interventions?

Key Question 5

What are the harms associated with treating children under 18 years of age for disruptive behaviors with either psychosocial or pharmacologic interventions?

Key Question 6

- Do interventions intended to address disruptive behaviors and identified in Key Questions 1-4 vary in effectiveness based on patient characteristics, including gender, age, race/ethnic minority, family history of disruptive behavior disorders, family history of mental health disorders, history of trauma, and socioeconomic status?

- Do interventions intended to address disruptive behaviors and identified in Key Questions 1-4 vary in effectiveness based on characteristics of the disorder, including specific disruptive behavior or disruptive behavior disorder (e.g., oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, aggression), concomitant psychopathology (e.g., attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or substance abuse), related personality traits and symptom clusters, presence of co-morbidities (other than concomitant psychopathology), age of onset, and duration?

- Do interventions intended to address disruptive behaviors and identified in Key Questions 1-4 vary in effectiveness based on treatment history of the patient?

- Do interventions intended to address disruptive behaviors and identified in Key Questions 1-4 vary in effectiveness based on characteristics of the treatment, including duration, delivery, timing, and dose?

Summary of Public Comments and Changes to Posted Key Questions

Overall, commenters agreed that the Key Questions are important and relevant to patients, families, and clinicians and capture the issues that often lead to decisional uncertainties. Comments affirmed that there exist wide variations in clinical management including the use of polypharmacy and variations of psychosocial therapy, administered with or without fidelity to a standard protocol. The summary of public comments included numerous recommendations for examination of patient, family, and intervention characteristics on treatment effects.

We anticipate using a broad definition of DBD, including conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder, but not limited to a DBD diagnosis. The defining feature of included studies will be that they focus on treatment of disruptive behavior as the primary treatment target. We will document diagnoses and consider whether the results can be stratified by diagnostic categories.

For Key Questions 1-4, we clarified that our approach is to include studies of children with disruptive behaviors; if the data allow, we will stratify the results along clinical groups and population age and group results to reflect what is found in the literature. We added inactive treatments and usual care (e.g., wait list controls, placebo, and treatment as usual) as eligible comparators. We added a separate Key Question for harms and adverse effects associated with interventions. We added family history to Key Question 6 (formerly Key Question 5) and plan to collect data on this and other variables reported in the studies to determine whether there are meaningful associations. We organized Key Question 6 to capture the evidence needed to synthesize information on patient characteristics, disorder characteristics, treatment history, and treatment interventions that can change the intervention effects.

PICOTS

| PICOTS | Criteria and Key Question(s) |

|---|---|

| Abbreviations: KQ=key question | |

| Population | Children under 18 years of age who are being treated for disruptive behavior or a disruptive behavior disorder. (KQs 1-6) |

| Intervention(s) |

|

| Comparator |

|

| Outcomes |

|

| Timing | Any length of followup (KQs 1-6) |

| Setting | Clinical setting, including medical or psychosocial care that is delivered to individuals by clinical professionals, as well as individually focused programs to which clinicians refer their patients. Excludes school wide or system wide settings wherein interventions are targeted more widely. (KQs 1-6) |

Case definition for disruptive behavior

Behaviors that “violate the rights of others (e.g., aggression, destruction of property) and/or that bring the individual into significant conflict with societal norms or authority figures.”1 The review will include studies that look at children exhibiting these behaviors as a primary problem, such as the DSM-5 disruptive behaviors disorders like Conduct Disorder, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, and Intermittent Explosive Disorder, though some studies will include subjects who have not been diagnosed with one of these disorders but who are being treated for disruptive behaviors such as early onset aggression. This review will exclude studies where disruptive behaviors are studied as symptoms or comorbidities (e.g., substance abuse, Autism Spectrum Disorder, Pervasive Developmental Disorder, developmental delay, intellectual disability, and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, etc.).

1American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Fifth edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. Available at: dsm.psychiatryonline.org

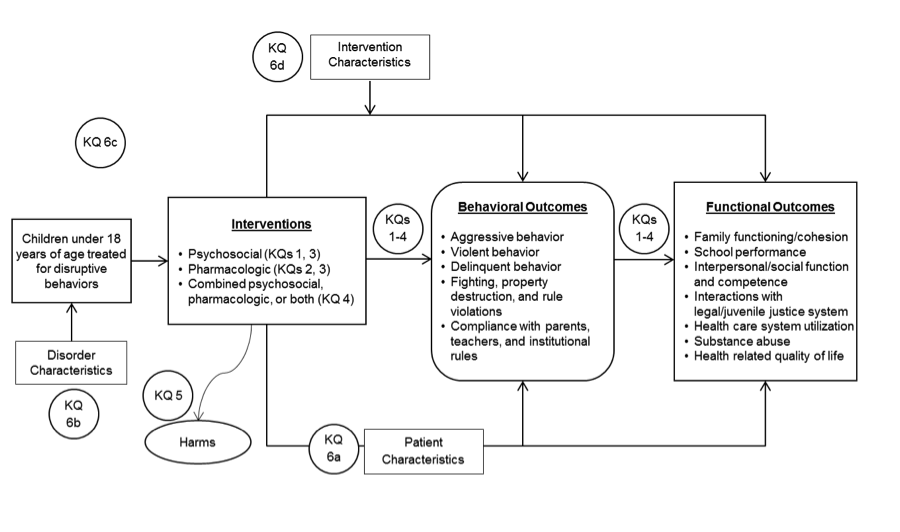

Analytic Framework

The analytic framework illustrates the population, interventions, outcomes, and adverse effects that will guide the literature search and synthesis.

Figure 1. Analytic framework

Methods

A. Criteria for Inclusion/Exclusion of Studies in the Review

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review are derived from our understanding of the literature, refinement of the review topic with the Task Order Officer and Key informants, and feedback on the Key Questions obtained during the public posting period.

Target population. The target population for this review is children under 18 years of age who are being treated for a disruptive behavior (see case definition). Eligible studies must focus on the treatment of the disruptive behavior and include children exhibiting disruptive behaviors as a primary problem (e.g., conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and intermittent explosive disorder), though some studies will include subjects who have not have been diagnosed with a disorder but who are being treated for disruptive behaviors such as early onset aggression.

We will exclude studies of disruptive behavior secondary to conditions in which disruptive behaviors are studied as symptoms or comorbidities (e.g., treatment of substance abuse, developmental delay, intellectual disability, pediatric bipolar disorder, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder).

We will include studies of interventions that target parents of children with a disruptive behavior if the study explicitly defines the eligible patient population to include a child with a disruptive behavior and the study reports one or more of the child outcomes specified below.

Interventions. This review will specifically focus on psychosocial and pharmacologic interventions for disruptive behavior. Combined or co-interventions may include combinations or pharmacologic agents or psychosocial intervention, or medication used in conjunction with psychosocial interventions. Parent-targeted psychosocial interventions will be included in the review if the study reports changes to child disruptive behavior.

Psychosocial interventions. For this review, we will consider studies of psychosocial interventions such as: behavior management training, social skills training; cognitive behavior therapy; functional behavioral interventions; parent training; dialectical behavior training; and contingency management methods. We will examine studies of educational interventions and family-focused interventions for inclusion. Studies of educational and parent- or family-focused interventions may be included if the study includes children with disruptive behavior and measures and reports at least one child behavior or functional outcome. We will include studies that evaluate an intervention targeting the health or well-being of the parent or caretaker of a child with DBD only if the study reports child outcomes. For the purposes of this review, psychosocial interventions do not include information technology-based and assisted services, media, diet or exercise; however, if reported as co-interventions, we will extract this information (see Data Extraction below).

We will not include studies of prevention in asymptomatic, undiagnosed, or at-risk patients. We will not include studies designed exclusively to assess, measure, screen, or diagnose disease or symptoms. We will not include universal interventions such as those implemented in the school setting, studies of systems-level interventions, or studies of interventions targeting organizational delivery of care.

Other excluded interventions include:

- Dietary supplements and specialized diets

- Allied health interventions (e.g., speech/language therapy, occupational, and physical therapy)

- Complementary and alternative medicine interventions (e.g., acupuncture, herbal and folk remedies)

- Physical activity and recreational programs (e.g., yoga, exercise training)

- Invasive medical interventions (e.g., surgery, deep brain stimulation)

Pharmacologic interventions. Eligible pharmacologic interventions include both FDA-approved medications for the treatment of a behavior disorder or management of disruptive behaviors in children and medications used off-label for disruptive behavior. We identified specific pharmacologic agents from the following broad classes of drugs: alpha-agonists, anticonvulsants, second-generation (i.e., atypical) antipsychotics, beta-adrenergic blocking agents (i.e., beta-blockers), central nervous system stimulants, first-generation antipsychotics, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, mood stabilizers, and antihistamines. We include a list of the specific pharmacologic agents (generic and brand names) in Appendix A.

Combined interventions. We will consider studies of a combined (i.e., co-administered, co-therapy, conjunctive, or adjunctive) intervention that includes one or more of the eligible psychosocial or pharmacologic interventions identified in Key Questions 1-3 or is a uniquely described combination intervention designed or implemented specifically to treat children with disruptive behavior.

Outcomes. For Key Questions 1-4 and 6, included studies must report at least one behavioral or functional outcome listed in the Analytic Framework. For Key Question 5, we will include studies that report harms (i.e., adverse effects) for an intervention included in Key Questions 1-4. For KQ 6, the outcomes are comparison of cases for specific variables identified in the section on data extraction below.

We will not include or exclude studies based on the effect size. Studies must report child outcomes. We will extract information on long-term outcomes when it is reported.

Setting. We are focusing on interventions in the clinical setting, including medical or psychosocial care that is delivered to individuals by clinical professionals, as well as individually focused programs to which clinicians refer their patients. We do not intend to limit the review by setting or provider other than to exclude studies that are exclusively in-patient (i.e., hospitalized) and studies of a systems-level intervention (e.g., delivered universally in the school or juvenile detention setting).

Study characteristics. Ideally, randomized controlled trials will be used to assess effectiveness of interventions. If there are too few RCTs available to make meaningful conclusions, we will include first non-randomized controlled clinical trials, then prospective and retrospective cohort studies. Case control studies are rarely optimal for assessing causal inferences or measuring treatment effects and will not be included; nor will studies without comparators (e.g. pre-post or case series). Harms will be collected from the studies included for effectiveness, plus cohort studies if only RCTs are used for the effectiveness questions, as well as through the grey literature search of the regulatory data.

If available, we will evaluate and incorporate the findings from existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses of relevant studies. If systematic reviews are included, we will update findings with any new primary studies identified in our searches. If multiple systematic reviews are relevant and low risk of bias, we will focus on the findings from the most recent reviews and evaluate areas of consistency and inconsistency across the reviews.

For Key Question 5, we will include adverse events and harms data (for interventions identified in Key Questions 1-4) from noncomparative study designs and regulatory reports to augment the harms data collected from the controlled prospective studies meeting the review inclusion criteria.

For all Key Questions, we will seek original data from primary study publications. We will include data from related publications, noting the study-related publications to avoid we will use data from existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses as primary sources of evidence if they address a Key Question and meet other PICOTS inclusion criteria.69

Eligible studies will not by limited by intervention timing or duration of followup, but we will limit the search to studies published in or after 1994. We conducted a preliminary screening of records retrieved from a search with no limits to the publication year. We screened approximately 1500 records published 20 or more years ago, and found that the study populations were inadequately described and poorly characterized, rendering a large number of the older studies unusable for this review. In order to include studies of patients meeting the population criteria for this review, the team agreed to limit the retrieval of primary study data to those studies published in or after 1994, as this date cutoff aligns with the availability of the DSM-IV.70

We will not specify a minimum sample size (i.e., number of participants per arm) for eligible studies. We will examine the appropriateness of each study for inclusion in a meta-analysis. Studies that are too heterogeneous or otherwise unsuitable to contribute data to the meta-analysis may be included as part of a narrative synthesis.

We plan to restrict this review to studies published in English-language papers. Key discipline specific publications from non-U.S. countries and international conferences present and publish material in English, minimizing the likelihood of language bias. However, we will assess abstracts that are for papers published in other languages to assess the robustness of this assumption.

B. Searching for the Evidence: Literature Search Strategies

Search strategy

The literature search strategies were developed by library scientists who work closely with the EPC project teams. Librarians and topic experts identified key subject terms for the population and interventions. We included broad terms for psychosocial interventions, as well as interventions by name (e.g., Parent-Child Interaction Therapy, Incredible Years Programs, and Positive Parenting Program). We included terms to describe drug classes and individual agents. We built the search strategies in tandem with the refinement of the Key Questions and Analytic Framework to ensure that the literature retrieval would be representative of the project scope. The search strategies (Appendix B) were reviewed by the team’s library scientist and preliminary results were vetted by clinical and methodologic subject matter experts.

Databases

To ensure comprehensive retrieval of relevant studies, we will use the following key databases: the MEDLINE medical literature database (via the PubMed interface), EMBASE, and PsycInfo®.

Hand searching

We will conduct hand searches of the reference lists from recent systematic reviews and relevant articles for additional studies that meet inclusion criteria. We will review the references lists from included relevant studies.

Grey literature

We will continue to search the Web sites of agencies/organizations conducting research or involved in policy or guidance in the area. These will include professional organizations such as the American Psychological Association, the American Psychiatric Association, SAMHSA, and the American Academy for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

We will also search other sources (e.g., Clinicaltrials.gov, meeting abstracts, the Food and Drug Administration) for context and relevant data, as well as ongoing trials. We will review and extract information from package inserts and unpublished data obtained by the Scientific Resource Center for all relevant drug interventions, to ascertain the completeness of the published data and to identify data specifically on harms and side effects.

Modifications and updates

As the team undertakes preliminary screening of full text papers, we anticipate the need for additional minor refinements and/or expansions to the search to ensure that the case definition is represented by the literature retrieval. We will document any modifications we make to the searches, retain the citations for all retrievals, and record the screening activity to capture inclusion/exclusion data.

During our review of abstracts and full-text articles, we will update the literature search quarterly and add relevant studies. We will update the literature search and add relevant studies while the draft report is undergoing peer review.

Contacts for Scientific Information Packets (SIPs)

We will request Scientific Information Packets (SIP) and regulatory information on individual pharmacologic agents listed as potential interventions from the Scientific Resource Center (SRC). The SRC SIP coordinator requests information from industry stakeholders and manages the information retrieval, preventing direct contact between the EPC working on the project and industry stakeholders. We include a list of the specific pharmacologic agents (generic and brand names) and known pharmaceutical companies in Appendix A.

Screening and extraction forms

We will develop forms for screening (abstract and full-text review) and data extraction. The team will test all screening and data collection forms using a sample of relevant articles. We will revise the forms, as needed, prior to commencing the next stage of screening or extraction.

The abstract review form will contain questions about the primary exclusion and inclusion criteria for initial screening. We will use a more detailed form (full-text screening form) when we examine the full-text of references that met criteria for inclusion in abstract review. In addition, we will use the full-text screening form to estimate the numbers of studies available to address individual Key Questions.

We will create data extraction forms to collect detailed information on the study characteristics, intervention(s), comparator(s), arm details, reported outcomes and outcome measures, and study quality. See the section “Data Extraction” below, for detailed descriptions of the data and information that we plan to extract from the studies. The extraction forms will include detailed instructions and labels to reinforce coding reliability and will consist of items with mutually exclusive and exhaustive answer options to promote consistency. The forms will include all the information necessary to generate summary tables, create evidence tables, and perform data synthesis.

Study selection

We will conduct two levels of screening using explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria. Initially, we will review the titles and abstracts from all references identified in the literature searches. References that meet the inclusion criteria as determined by one reviewer will be promoted for the second level screening. Two reviewers must determine independently that a study does not meet all inclusion criteria in order to be excluded at the abstract screening level. Conflicts will be promoted for a second level review (i.e., full text review) as will references with insufficient information to make a decision about eligibility. All references promoted to full text review will be screened by at least two reviewers against the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Discrepancies will be resolved by a senior team member or through team consensus.

C. Data Abstraction and Data Management

Data extraction

As described above, we will develop forms to classify and describe study elements and assess the quality of the study. We will test the data extraction forms using a sample of included studies. We will revise the forms as needed to ensure that the forms are comprehensive and representative of the range of data anticipated. A senior level team member will review the data extraction against the original articles for quality control. The study and data abstraction forms will be used to develop summary tables for the individual studies and across selected groups of studies.

We will record study characteristics, study participant characteristics, intervention characteristics, outcomes, modifiers of treatment effect and study quality from each included study. We will flag related publications and extract nonduplicate study data. We will note data elements not reported or unavailable from the primary or related study publications.

Study characteristics. We will collect and record descriptive data for each of the studies that meet the full text screening criteria including study design, year, location, setting, randomization, blinding, inclusion and exclusion criteria, intervention characteristics, and related publications. We will record source of funding and authors’ competing interest disclosures for all studies included in the review.

Patient characteristics.We will collect patient (or subject) demographics and characteristics reported in the included studies, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, diagnosis, symptoms, and severity, weight/body mass index, history or trauma, cognitive function, and treatment history. In addition to these patient characteristics, we will extract data on specific patient-related variables that may modify or mediate treatment effects. These potential modifiers of treatment effect are listed in the section below (Modifiers) under Key Question 6a.

Intervention characteristics.We will record intervention characteristics and components in detail.

The following will be extracted if reported in the included studies:

- Resources used to deliver the intervention (training, parental participation, financial resources, etc.)

- Intervention delivery (e.g., format, qualifications of the person delivering the intervention)

- Co-interventions

- Dose, frequency, and duration of pharmacologic and psychosocial interventions

- Intervention duration and schedule

- Titration schedule

- Components of the intervention

- Intervention delivery setting

In addition to the intervention descriptions of the included studies, we will extract data on treatment components and intervention characteristics that may modify or mediate treatment effects. These potential modifiers of treatment effect are listed in the section below (Modifiers) under Key Question 6d.

Outcomes. There are numerous potentially relevant outcomes. We categorized outcomes broadly as behavioral or functional and presented a preliminary list of outcomes to Key informants.

- Behavioral outcomes

- Aggressive behavior

- Violent behavior

- Delinquent behavior

- Fighting, property destruction, and rule violations

- Compliance with parents, teachers, and institutional rules

- Functional outcomes

- Family functioning/ cohesion

- School performance

- Interpersonal/social function and competence

- Interactions with legal/juvenile justice system

- Health care system utilization

- Substance abuse

- Health related quality of life

We will extract the measures used to report the target outcomes and will comment on the reported validity of measures when the information is available. We will include broad measures of quality of life and social functioning.

For Key Question 5, we will extract data on the harms and/or adverse effects associated with any intervention addressed by Key Questions 1-4. The review will identify and analyze the evidence for harms of pharmacologic interventions used to treat disruptive behavior. We will extract harms data reported in the grey literature, including integrated safety reports from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s regulatory documents.

Potential adverse effects / harms of pharmacologic interventions include:

- Metabolic effects: weight gain, hyperglycemia and diabetes, hyperlipidemia

- Extrapyramidal adverse effects: parkinsonism, acute dystonia, akathisia, tardive dyskinesia

- Cardiac effects: prolonged QT/arrhythmias, hypotension, cardiomyopathy

- Prolactin-related effects

- Allergic reaction

- Sudden death

- Suicide

- Over-medication or inappropriate medication

- Other harms, as reported

The review will also identify potential harms of psychosocial interventions as reported in the literature, which may include:

- Negative effects on family dynamics

- Stigma

Modifiers. To address Key Question 6, we will record potential modifiers to determine whether these variables affect treatment response (Table 2). We anticipate that patient age and certain disorder characteristics (such as disease severity) will be robust predictors of outcomes.

We will also extract information on intervention delivery, intervention setting, and environmental factors (e.g., parental engagement) that may account for variations in observed treatment effects. The potential modifiers in Table 2 represent categories of variables that may be linked to treatment effects. We will extract the reported variables from included studies and organize into meaningful groups (e.g., maternal depression and paternal aggression may be included under family history of mental health conditions, but will be reported individually).

| Key Questions | Treatment Effect Modifiers |

|---|---|

| Patient characteristics (KQ 6a) |

|

| Disorder characteristics (KQ 6b) |

|

| Treatment history (KQ6c) | Treatment history: any |

| Intervention characteristics (KQ6d) |

|

Data Management

We will create forms for screening and for recording study information and outcome data. We will use DistillerSR (Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Canada) for screening references. We will deposit the data used in the meta-analyses into the Systematic Review Data Repository (SRDR) system. We will register the final protocol with PROSPERO, an international database of prospectively registered systematic reviews in health and social care.

D. Assessment of Methodological Risk of Bias of Individual Studies

We will assess the risk of bias of studies for the outcomes of interest specified in the PICOTS above using criteria from established tools and the Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews.71 Two senior investigators will independently assess each included study. Disagreements between assessors will be resolved through discussion.

We will use the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool72 to assess risk of bias for randomized controlled trials of effectiveness. The tool includes six items from five domains of potential sources of bias (i.e., selection, reporting, performance, detection, attrition, and other) and an item for other sources of bias. We will specifically assess for detection bias by evaluating outcome measurement and assessment methods to detect effects. Additional items may be necessary to evaluate potential risk of bias associated with fidelity for psychosocial interventions.

To assess risk of bias for study designs other than RCTs, we will use the Newcastle Ottawa Scale38 or the RTI Item Bank73 for cohort studies, and the AMSTAR tool for systematic reviews and meta-analyses74-76 To assess the risk of bias associated with the reporting of harms, we will use the McMaster Assessment of Harms Tool.77

We will give studies an overall rating of low, moderate, or high risk of bias. We intend to exclude entirely studies with a fatal flaw (i.e., a deficit of design or conduct that compromises the validity of the study and cannot be remedied) from the review. This may include for example, using an inappropriate measure to measure a primary outcome or key construct. We will conduct a sensitivity analysis to test the effect of excluding studies judged to have a high risk of bias from any quantitative synthesis, and will assess the implications qualitatively if we do not perform a meta-analysis.

E. Data Synthesis

Synthesizing results

Our preliminary assessment of the literature suggests that we may be able to use meta-analytic techniques after transforming outcomes into standardized measures in order to assess effectiveness. This approach will have the benefit of allowing us to combine studies that use different specific measures for the same outcomes; it suffers to some degree in clinical interpretability but our clinical experts will assist in placing meta-analytic results in context for our end users. The specific meta-analysis or meta-regression will depend on the data available.

We will refine our analytic approach as we gather more data on the available literature. It is most likely that analyses will be combined using a hierarchical mixed effects model. The random effects in such a model will allow both an estimate of the overall (population) effect as well as an estimate of the variance of the effect across studies, after controlling for available study-level covariates. This is preferable to the use of an arbitrary variance cutoff value or statistical tests for heterogeneity, such as Q statistics or I2 scores.

The decision of whether to partially pool a set of studies using random effects depends not on how heterogeneous their outcomes are, but rather, whether they can be considered exchangeable studies from a population of studies of the same phenomenon. This should be determined based on the design and quality of the studies, independently of the studies’ relative effect sizes.

Some differences among study populations may be accounted for in the model by adjusting for factors such as age and gender distributions and the prevalence of concomitant conditions in the study sample. Newer approaches to random effects meta-analysis allow for robust (e.g., non-parametric) estimates of variation that do not rely on the assumption of normally-distributed random effects. This permits us to account for “outlier” studies in the meta-analytic model without either discarding them unnecessarily or allowing them to disproportionately influence meta-estimates.

As an example, a primary metric for evaluating interventions is the change in disruptive behaviors for any given intervention, relative to usual care. We anticipate that due to fundamental differences among classes of interventions (e.g., psychotherapy, parent training, pharmacology) we will use separate meta-analytic models for each. Within intervention classes, however, it may be possible to pool subsets of studies, conditional on a suite of covariates that, when properly modeled, can be considered exchangeable (conditionally independent given a set of study-level covariates).

Care must be taken in assigning the membership of each study to one of a reasonably small set of intervention classes. It will be important to test the sensitivity of our meta-analytic models to misclassification error, or to pooling studies into classes that are too heterogeneous (i.e., too few classes in the set).

Analysis of subgroups will be done formally, within a statistical model, or by stratifying results and organizing the report in such a way that end users are provided with both overall outcomes data and information specific to subgroups that can be easily identified and stand alone as needed. Subgroup analysis may be used to evaluate the intervention effect in a defined subset of the participants in a trial, or in complementary subsets. Subgroup analysis can be undertaken in a variety of ways, from completely separate models at one extreme, to simply including a subgroup covariate in a single model at the other, with multilevel and random effects models somewhere in the middle.78,79 Generally, trial sizes are too small for sub-group analyses within individual studies to have adequate statistical power.

Meta-regression models describe associations between the summary effects and study-level data, that is, it describes only between-study, not between-patient variation. We would use multilevel models, which boost the power of the analysis by sharing strengths across subgroups for variables where it makes sense to do so, or subgroup analysis (with random effects meta-analysis) to explore heterogeneity if there are a sufficient number of studies. When the sizes of the included studies are moderate or large, each subgroup should have at least 6 to 10 studies for a continuous study-level variable and a minimum of four studies for a categorical study-level variable. These numbers serve as a rule of thumb for the lower bound for number of studies that investigators would consider for a meta-regression, but power will vary according to the size and variability of the effect.

Since we are interested in mixed-treatment comparisons across classes of interventions, it is natural to consider whether inferences may be obtained indirectly, via network meta-analysis (NMA). Thus, in addition to direct evidence for the effectiveness of a given intervention relative to another among studies that make the same comparison, NMA allows for the comparison of different classes of intervention based on the presence of a common comparator among the studies. This approach introduces an additional source of uncertainty into the meta-analysis, namely the potential for incompatibility between direct and indirect comparisons, which can be accommodated by the statistical model. Recent advances Bayesian NMA methods allow these indirect effects to be estimated by treating outcomes from interventions not undertaken by a particular study as missing data. Because of the potential benefit for learning more about the comparative effectiveness of DBD interventions through indirect information, we will consider a NMA approach if the number of studies is large enough to power such an analysis.

F. Grading the Strength of Evidence

Strength of evidence assessments

We will use the recommendations from AHRQ methods guidance and updated guidance for grading the strength of body of evidence.80,81 In accordance with the methods guidance, we will first assess and grade “domains” and then combine domain scores into an overall grade.

We will use established concepts of the quantity of evidence (e.g., numbers of studies, aggregate ending-sample sizes), the quality of evidence (from the quality ratings on individual articles), and the coherence or consistency of findings across similar and dissimilar studies and in comparison to known or theoretically sound ideas of clinical or behavioral knowledge. We will make these judgments as appropriate for each Key Question.

Two senior staff will independently grade the body of evidence; disagreements will be resolved as needed through discussion or third-party adjudication. We will record strength of evidence assessments in tables, summarizing for each outcome.

Individual comparisons and outcomes

We will give an overall evidence grade based on the ratings for the individual domains for each key outcome. We will assess strength of evidence for the direction or estimate of effect for the behavioral and functional outcomes from the PICOTS above for the treatment comparisons in Key Questions 1-4.

The required domains for grading the strength of evidence are: study limitations (previously named risk of bias), directness, consistency, and precision. The fifth required domain is reporting bias, which includes publication bias, selective outcome reporting, and selective analysis reporting. A set of domains supplement the five required domains: dose-response association, plausible confounding, and strength of association (i.e., magnitude of effect). These additional domains are most relevant to bodies of evidence consisting of observational studies, but do apply to RCTs and will be reported when relevant to strengthen the strength of evidence assessment.

When scoring the individual domains, we will reference the definitions and scores outlined in AHRQ's updated guidance for grading the strength of a body of evidence.80

When a quantitative synthesis is precluded, we will assess the domains of precision and consistency, through discussion and consensus between the team’s lead investigators and methodologic expert.

Overall strength of evidence

We will characterize the overall strength of evidence by combining the individual domain scores. We will use one of four grades intended to represent the investigators’ confidence in the body of evidence for a given outcome’s direction or summary estimate of effect.

Table 3 is adapted from AHRQ's updated guidance for grading the strength of a body of evidence80 and summarizes the four grades that we will use for the overall assessment of the body of evidence. Grades are denoted high, moderate, low, and insufficient. When no studies are available for an outcome or comparison of interest, we will grade the evidence as insufficient.

| Grade | Definition |

|---|---|

| High | We are very confident that the estimate of effect lies close to the true effect for this outcome. The body of evidence has few or no deficiencies. We believe that the findings are stable, i.e., another study would not change the conclusions. |

| Moderate | We are moderately confident that the estimate of effect lies close to the true effect for this outcome. The body of evidence has some deficiencies. We believe that the findings are likely to be stable, but some doubt remains. |

| Low | We have limited confidence that the estimate of effect lies close to the true effect for this outcome. The body of evidence has major or numerous deficiencies (or both). We believe that additional evidence is needed before concluding either that the findings are stable or that the estimate of effect is close to the true effect. |

| Insufficient | We have no evidence, we are unable to estimate an effect, or we have no confidence in the estimate of effect for this outcome. No evidence is available or the body of evidence has unacceptable deficiencies, precluding reaching a conclusion. |

G. Assessing Applicability

We will assess the relevance and applicability of the findings to the dilemmas and uncertainties that challenge providers and families seeking treatment for children with disruptive behavior. We will extract and summarize common features of the study population. We will document diagnoses and consider whether the results can be stratified by severity, comorbidity, or age. We will assess how patient age, treatment history, co-occurring diagnoses, and symptom severity are reported in the included studies and the degree to which the populations studied reflect the target population for practice. Many children with disruptive behavior are treated in primary care. Interventions developed and tested in academic medical centers may differ from interventions evaluated in health departments and other community clinical settings.

Resource-poor environments may be limited in the options and types of interventions available. It will be important to characterize the resources needed including types of providers or involvement of nonclinical providers or families to implement effective interventions and provide the end users with adequate data on feasibility and implementation planning.

In addition to patient and interventions characteristics, other aspects of the patient’s environment (e.g., parental participation, or social relationships) are likely to affect treatment success rates; where possible, we will extract those data. Where the data are not presented in the research, we will comment on the degree to which environmental factors may have affected outcomes. We will use the applicability assessment to frame the discussion on future research and encourage researchers to capture these important data.

References

- Lahey BB, Loeber R, Burke J, et al. Adolescent outcomes of childhood conduct disorder among clinic-referred boys: predictors of improvement. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2002 Aug;30(4):333-48. PMID: 12108765

- The Chance of a Lifetime: Preventing Early Conduct Problems and Reducing Crime. London: Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health; 2009.

- Loeber R. Oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder. Hosp Community Psychiatry. 1991 Nov;42(11):1099-100, 102. PMID: 1743634

- Frick PJ, Kamphaus RW, Lahey BB, et al. Academic underachievement and the disruptive behavior disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991 Apr;59(2):289-94. PMID: 2030190

- Loeber R. Antisocial behavior: more enduring than changeable? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1991 May;30(3):393-7. PMID: 2055875

- Loeber R, Green SM, Lahey BB, et al. Differences and similarities between children, mothers, and teachers as informants on disruptive child behavior. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1991 Feb;19(1):75-95. PMID: 2030249

- Loeber R, Lahey BB, Thomas C. Diagnostic conundrum of oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991 Aug;100(3):379-90. PMID: 1918617

- Meier MH, Slutske WS, Heath AC, et al. Sex differences in the genetic and environmental influences on childhood conduct disorder and adult antisocial behavior. J Abnorm Psychol. 2011 May;120(2):377-88. PMID: 21319923

- Murrihy RC, Kidman AD, Ollencisk TH. Clinical handbook of assessing and treating conduct problems in youth. New York: Springer Science Business Media; 2010.

- Kutcher S, Aman M, Brooks SJ, et al. International consensus statement on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and disruptive behaviour disorders (DBDs): clinical implications and treatment practice suggestions. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2004 Jan;14(1):11-28. PMID: 14659983

- Lahey BB, Miller TL, Gordon RA, et al. Developmental epidemiology of the disruptive behavior disorders. In: Quay HC, Hogan AE, eds. Handbook of Disruptive Behavior Disorder. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1999.

- Maughan B, Rowe R, Messer J, et al. Conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder in a national sample: developmental epidemiology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004 Mar;45(3):609-21. PMID: 15055379

- Loeber R, Burke JD, Lahey BB, et al. Oppositional defiant and conduct disorder: a review of the past 10 years, part I. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000 Dec;39(12):1468-84. PMID: 11128323

- Burke JD, Loeber R, Birmaher B. Oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder: a review of the past 10 years, part II. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002 Nov;41(11):1275-93. PMID: 12410070

- Bonin EM, Stevens M, Beecham J, et al. Costs and longer-term savings of parenting programmes for the prevention of persistent conduct disorder: a modelling study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:803. PMID: 21999434

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;62(6):593-602. PMID: 15939837

- Russo MF, Loeber R, Lahey BB, et al. Oppositional Defiant and Conduct Disorders - Validation of the DSMIII-R and an Alternative Diagnostic Option. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1994 Mar;23(1):56-68.

- Russo MF, Beidel DC. Comorbidity of Childhood Anxiety and Externalizing Disorders - Prevalence, Associated Characteristics, and Validation Issues. Clinical Psychology Review. 1994;14(3):199-221. PMID: WOS:A1994NT70500003

- U. S. Department of Health and Human Services. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health; 1999.

- McKinney C, Morse M. Assessment of Disruptive Behavior Disorders: Tools and Recommendations. Professional Psychology-Research and Practice. 2012 Dec;43(6):641-9.

- van Goozen SH, Matthys W, Cohen-Kettenis PT, et al. Salivary cortisol and cardiovascular activity during stress in oppositional-defiant disorder boys and normal controls. Biol Psychiatry. 1998 Apr 1;43(7):531-9. PMID: 9547933

- Loeber R, Green SM, Lahey BB, et al. Findings on disruptive behavior disorders from the first decade of the Developmental Trends Study. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2000 Mar;3(1):37-60. PMID: 11228766

- Latimer K, Wilson P, Kemp J, et al. Disruptive behaviour disorders: a systematic review of environmental antenatal and early years risk factors. Child Care Health Dev. 2012 Sep;38(5):611-28. PMID: 22372737

- Loeber R, Burke JD, Pardini DA. Development and etiology of disruptive and delinquent behavior. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2009;5:291-310. PMID: 19154139

- August GJ, Bloomquist ML, Lee SS, et al. Can evidence-based prevention programs be sustained in community practice settings? The Early Risers' Advanced-Stage Effectiveness Trial. Prev Sci. 2006 Jun;7(2):151-65. PMID: 16555143

- Bloomquist ML, August GJ, Horowitz JL, et al. Moving from science to service: transposing and sustaining the Early Risers prevention program in a community service system. J Prim Prev. 2008 Jul;29(4):307-21. PMID: 18581235

- Knapp M, McDaid D, Parsonage M, eds. Mental health promotion and mental illness prevention: The economic case. London: Department of Health; 2011.

- Cooper WO, Arbogast PG, Ding H, et al. Trends in prescribing of antipsychotic medications for US children. Ambul Pediatr. 2006;6:79-83. PMID: 16530143

- Cooper WO, Federspiel CF, Griffin MR, et al. New use of anticonvulsant medications among children enrolled in the Tennessee Medicaid Program. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151(12):1242-6. PMID: 9412601

- Cooper WO, Hickson GB, Fuchs C, et al. New users of antipsychotic medications among children enrolled in TennCare. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:753-9. PMID: 15289247

- Henggeler SW, Melton GB, Smith LA. Family preservation using multisystemic therapy: an effective alternative to incarcerating serious juvenile offenders. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992 Dec;60(6):953-61. PMID: 1460157

- Alexander J, Parsons BV. Functional Family Therapy. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole; 1982.

- Wells KC, Egan J. Social learning and systems family therapy for childhood oppositional disorder: comparative treatment outcome. Compr Psychiatry. 1988 Mar-Apr;29(2):138-46. PMID: 3370964

- Hembree-Kigin TL, McNeil CB. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy. New Yotk: Plenum Press; 1995.

- Kazdin AE, Siegel TC, Bass D. Cognitive problem-solving skills training and parent management training in the treatment of antisocial behavior in children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992 Oct;60(5):733-47. PMID: 1401389

- Cunningham NR, Ollendick TH. Comorbidity of anxiety and conduct problems in children: implications for clinical research and practice. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2010 Dec;13(4):333-47. PMID: 20809124

- Kolko DJ, Pardini DA. ODD dimensions, ADHD, and callous-unemotional traits as predictors of treatment response in children with disruptive behavior disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2010 Nov;119(4):713-25. PMID: 21090875

- Goldstein AP, Glick B, Gibbs JC. Aggression replacement training: A comprehensive intervention for aggressive youth; Revised Edition. Champaign, IL: Research Press; 1998.

- Comer JS, Chow C, Chan PT, et al. Psychosocial treatment efficacy for disruptive behavior problems in very young children: a meta-analytic examination. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013 Jan;52(1):26-36. PMID: 23265631

- Tcheremissine OV, Lieving LM. Pharmacological aspects of the treatment of conduct disorder in children and adolescents. CNS Drugs. 2006;20(7):549-65. PMID: 16800715

- Newcorn JH, Ivanov I. Psychopharmacologic treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and disruptive behavior disorders. Pediatr Ann. 2007 Sep;36(9):564-74. PMID: 17910204

- Connor DF, Glatt SJ, Lopez ID, et al. Psychopharmacology and aggression. I: A meta-analysis of stimulant effects on overt/covert aggression-related behaviors in ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002 Mar;41(3):253-61. PMID: 11886019

- Linton D, Barr AM, Honer WG, et al. Antipsychotic and psychostimulant drug combination therapy in attention deficit/hyperactivity and disruptive behavior disorders: a systematic review of efficacy and tolerability. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013 May;15(5):355. PMID: 23539465

- Duhig MJ, Saha S, Scott JG. Efficacy of risperidone in children with disruptive behavioural disorders. J Paediatr Child Health. 2013 Jan;49(1):19-26. PMID: 22050179

- Hanwella R, Senanayake M, de Silva V. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of methylphenidate and atomoxetine in treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:176. PMID: 22074258

- Hazell PL, Kohn MR, Dickson R, et al. Core ADHD symptom improvement with atomoxetine versus methylphenidate: a direct comparison meta-analysis. J Atten Disord. 2011 Nov;15(8):674-83. PMID: 20837981

- Loy JH, Merry SN, Hetrick SE, et al. Atypical antipsychotics for disruptive behaviour disorders in children and youths. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9:CD008559. PMID: 22972123

- McKinney C, Renk K. Atypical antipsychotic medications in the management of disruptive behaviors in children: safety guidelines and recommendations. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011 Apr;31(3):465-71. PMID: 21130552

- Pringsheim T, Gorman D. Second-generation antipsychotics for the treatment of disruptive behaviour disorders in children: a systematic review. Can J Psychiatry. 2012 Dec;57(12):722-7. PMID: 23228230

- Seida JC, Schouten JR, Boylan K, et al. Antipsychotics for children and young adults: a comparative effectiveness review. Pediatrics. 2012 Mar;129(3):e771-84. PMID: 22351885

- van Wyk GW, Hazell PL, Kohn MR, et al. How oppositionality, inattention, and hyperactivity affect response to atomoxetine versus methylphenidate: a pooled meta-analysis. J Atten Disord. 2012 May;16(4):314-24. PMID: 21289234

- Bloch MH, Qawasmi A. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation for the treatment of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptomatology: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011 Oct;50(10):991-1000. PMID: 21961774

- Dretzke J, Davenport C, Frew E, et al. The clinical effectiveness of different parenting programmes for children with conduct problems: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2009;3(1):7. PMID: 19261188

- Furlong M, McGilloway S, Bywater T, et al. Cochrane review: behavioural and cognitive-behavioural group-based parenting programmes for early-onset conduct problems in children aged 3 to 12 years (Review). Evid Based Child Health. 2013 Mar 7;8(2):318-692. PMID: 23877886

- Lee MS, Choi TY, Kim JI, et al. Acupuncture for treating attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chin J Integr Med. 2011 Apr;17(4):257-60. PMID: 21509667

- Lee PC, Niew WI, Yang HJ, et al. A meta-analysis of behavioral parent training for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Res Dev Disabil. 2012 Nov-Dec;33(6):2040-9. PMID: 22750360

- Michelson D, Davenport C, Dretzke J, et al. Do evidence-based interventions work when tested in the "real world?" a systematic review and meta-analysis of parent management training for the treatment of child disruptive behavior. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2013 Mar;16(1):18-34. PMID: 23420407

- Sonuga-Barke EJ, Brandeis D, Cortese S, et al. Nonpharmacological interventions for ADHD: systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials of dietary and psychological treatments. Am J Psychiatry. 2013 Mar 1;170(3):275-89. PMID: 23360949

- Storebo OJ, Skoog M, Damm D, et al. Social skills training for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in children aged 5 to 18 years. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011(12):CD008223. PMID: 22161422

- Weisz JR, Kuppens S, Eckshtain D, et al. Performance of evidence-based youth psychotherapies compared with usual clinical care: a multilevel meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013 Jul;70(7):750-61. PMID: 23754332

- Zwi M, Jones H, Thorgaard C, et al. Parent training interventions for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in children aged 5 to 18 years. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011(12):CD003018. PMID: 22161373

- Knapp P, Chait A, Pappadopulos E, et al. Treatment of maladaptive aggression in youth: CERT guidelines I. Engagement, assessment, and management. Pediatrics. 2012 Jun;129(6):e1562-76. PMID: 22641762

- Scotto Rosato N, Correll CU, Pappadopulos E, et al. Treatment of maladaptive aggression in youth: CERT guidelines II. Treatments and ongoing management. Pediatrics. 2012 Jun;129(6):e1577-86. PMID: 22641763

- Vitiello B, Correll C, van Zwieten-Boot B, et al. Antipsychotics in children and adolescents: increasing use, evidence for efficacy and safety concerns. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009 Sep;19(9):629-35. PMID: 19467582

- Seida JC, Schouten JR, Mousavi SS, et al. First- and Second-Generation Antipsychotics for Children and Young Adults. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 39. AHRQ Publication No.: 11(12)-EHC077-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Feb 2012. https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/antipsychotics-children/research/

- Burns B, Fisher S, Ganju V, et al. Evidence-based and promising practices: Interventions for disruptive behavior disorders. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2011. https://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content/SMA11-4634CD-DVD/EBPsPromisingPractices-IDBD.pdf

- Charach A, Dashti B, Carson P, et al. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Effectiveness of Treatment in At-Risk Preschoolers; Long-Term Effectiveness in All Ages; and Variability in Prevalence, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Comparative Effectiveness Review No. 44. AHRQ Report No.: 12-EHC003-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; October 2011. https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/adhd/research/

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-IV-R. Fourth, revised. Washington, D. C.: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

- Whitlock EP, Lin JS, Chou R, et al. Using existing systematic reviews in complex systematic reviews. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2008 May 20;148(10):776-U103. PMID: 18490690

- American Psychiatric Association. Task Force on DSM-IV. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-IV. Fourth. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

- Viswanathan M, Ansari MT, Berkman ND, et al. Assessing the Risk of Bias of Individual Studies in Systematic Reviews of Health Care Interventions. AHRQ Publication No. 12-EHC047-EF. Rockville MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; March 2012. https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/methods-guidance-bias-individual-studies/methods/

- Higgins JP, Altman DG, Sterne JA. Chapter 8: Assessing the risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JP, Green S, eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011.

- Viswanathan M, Berkman ND. Development of the RTI item bank on risk of bias and precision of observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012 Feb;65(2):163-78. PMID: 21959223

- Shea BJ, Hamel C, Wells GA, et al. AMSTAR is a reliable and valid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009 Oct;62(10):1013-20. PMID: 19230606

- Shea BJ, Grimshaw JM, Wells GA, et al. Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7:10. PMID: 17302989

- Shea BJ, Bouter LM, Peterson J, et al. External validation of a measurement tool to assess systematic reviews (AMSTAR). PLoS One. 2007;2(12):e1350. PMID: 18159233

- Chou R, Aronson N, Atkins D, et al. AHRQ series paper 4: assessing harms when comparing medical interventions: AHRQ and the effective health-care program. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010 May;63(5):502-12. PMID: 18823754

- Fu R, Gartlehner G, Grant M, et al. Conducting quantitative synthesis when comparing medical interventions: AHRQ and the Effective Health Care Program. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011 Nov;64(11):1187-97. PMID: 21477993

- Sun X, Briel M, Busse JW, et al. Subgroup Analysis of Trials Is Rarely Easy (SATIRE): a study protocol for a systematic review to characterize the analysis, reporting, and claim of subgroup effects in randomized trials. Trials. 2009;10:101. PMID: 19900273

- Berkman ND, Lohr KN, Ansari MT, et al. Grading the strength of a body of evidence when assessing health care interventions for the effective health care program of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: An update. Methods Guide for Comparative Effectiveness Reviews (Prepared by the RTI-UNC Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No 290-2007-10056-I). AHRQ Publication No. 13(14)-EHC 130-EF. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; November 2013. https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/methods-guidance-grading-evidence/methods/

- Owens DK, Lohr KN, Atkins D, et al. AHRQ series paper 5: grading the strength of a body of evidence when comparing medical interventions--agency for healthcare research and quality and the effective health-care program. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010 May;63(5):513-23. PMID: 19595577

Definition of Terms

Not applicable.

Summary of Protocol Amendments

Not applicable.

Review of Key Questions

Key informants are the end users of research, including patients and caregivers, practicing clinicians, relevant professional and consumer organizations, purchasers of health care, and others with experience in making health care decisions. Within the EPC program, the key informant role is to provide input into identifying the Key Questions for research that will inform healthcare decisions. The EPC solicits input from key informants when developing questions for systematic review or when identifying high priority research gaps and needed new research. Key informants are not involved in analyzing the evidence or writing the report and have not reviewed the report, except as given the opportunity to do so through the peer or public review mechanism.

Key informants must disclose any financial conflicts of interest greater than $10,000 and any other relevant business or professional conflicts of interest. Because of their role as end-users, individuals are invited to serve as key informants and those who present with potential conflicts may be retained. The Task Order Officer and the EPC work to balance, manage, or mitigate any potential conflicts of interest identified.

Technical Experts

Technical experts comprise a multi-disciplinary group of clinical, content, and methodologic experts who provide input in defining populations, interventions, comparisons, or outcomes as well as identifying particular studies or databases to search. They are selected to provide broad expertise and perspectives specific to the topic under development. Divergent and conflicted opinions are common and perceived as health scientific discourse that results in a thoughtful, relevant systematic review. Therefore study questions, design and/or methodological approaches do not necessarily represent the views of individual technical and content experts. Technical experts provide information to the EPC to identify literature search strategies and recommend approaches to specific issues as requested by the EPC. Technical experts do not do analysis of any kind nor contribute to the writing of the report and have not reviewed the report, except as given the opportunity to do so through the peer or public review mechanism.

Technical experts must disclose any financial conflicts of interest greater than $10,000 and any other relevant business or professional conflicts of interest. Because of their unique clinical or content expertise, individuals are invited to serve as technical experts and those who present with potential conflicts may be retained. The Task Order Officer and the EPC work to balance, manage, or mitigate any potential conflicts of interest identified.

Peer Reviewers

Peer reviewers are invited to provide written comments on the draft report based on their clinical, content, or methodologic expertise. Peer review comments on the preliminary draft of the report are considered by the EPC in preparation of the final draft of the report. Peer reviewers do not participate in writing or editing of the final report or other products. The synthesis of the scientific literature presented in the final report does not necessarily represent the views of individual reviewers. The dispositions of the peer review comments are documented and will be published three months after the publication of the Evidence report.

Potential reviewers must disclose any financial conflicts of interest greater than $10,000 and any other relevant business or professional conflicts of interest. Invited peer reviewers may not have any financial conflict of interest greater than $10,000. Peer reviewers who disclose potential business or professional conflicts of interest may submit comments on draft reports through the public comment mechanism.

EPC Team Disclosures

EPC core team members must disclose any financial conflicts of interest greater than $1,000 and any other relevant business or professional conflicts of interest. Related financial conflicts of interest, which cumulatively total greater than $1,000, will usually disqualify EPC core team investigators.

Role of the Funder

This project was funded under Contract No. HHSA 290201200009I from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Task Order Officer reviewed contract deliverables for adherence to contract requirements and quality. The authors of this report are responsible for its content. Statements in the report should not be construed as endorsement by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Appendixes

Appendix A

Contacts for Scientific Information Packets (SIPs)

We have listed known pharmaceutical companies and other professional entities or researchers from whom Scientific Information Packets (SIP) will be requested at the time of finalizing the protocol. The drug classes considered are: alpha-agonists, anticonvulsants, second-generation (i.e., atypical) antipsychotics, beta-adrenergic blocking agents (i.e., beta-blockers), central nervous system (CNS) stimulants, first-generation antipsychotics, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI), and specific drugs from other class such as mood stabilizers and antihistamines.

Appendix B

- Table B-1: PubMed search strategy (10/08/13)

- Table B-2: PsycInfo® search strategy (10/08/13)

- Table B-3: PubMed search strategy (11/26/13)

- Table B-4: PsycInfo® search strategy (11/26/13)

- Table B-5: PubMed search strategy (12/11/13)

- Table B-6: PubMed search strategy (1/13/14)

- Table B-7: Embase search strategy (4/14/14)

Database: PubMed, PsycInfo® (viaProquest)

Date: October 8, 2013

We combined the retrievals from a scan of the literature for trials of disruptive behavior disorder from PubMed (Table B-1) and PsycInfo® (Table B-2). We retained 862 non-duplicate references.

Databases: PubMed, PsycInfo® (via Proquest)

Date: November 26, 2013

Following discussions with Key Informants, we revised the search strategy to include additional keyword terms for the population and interventions. We expanded the literature search from studies of individuals with a diagnosed disruptive behavior disorder to studies of individuals with disruptive behavior (i.e., characterized by aggressive or externalizing behavior). We also revised the preliminary search to capture variations of psychosocial treatment by including controlled vocabulary and keywords for specific behavioral interventions and programs. Table B-3 presents the detailed search terms and results from PubMed.

It is important to search and obtain the non-duplicate references from a behavioral medicine literature database such as PsycInfo®. Before applying date, age, and study design limits, we retrieved approximately 2,200 citations in PsycInfo®. About one third of these were specific to pharmacotherapy (Table B-4).